Large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable abilities in answering exam questions that often perplex human students, yet a recent study reveals a critical gap in how these AI systems perceive question difficulty. Conducted by a team of researchers from various US universities, the study sought to determine LLMs’ capability to evaluate exam question difficulty from a human perspective, using over 20 models, including GPT-5, GPT-4o, and various versions of Llama and Qwen.

The researchers tasked these models with estimating how challenging exam questions would be for human test-takers, comparing their outputs against actual difficulty ratings derived from student performance on the USMLE (medical), Cambridge (English), SAT Reading/Writing, and SAT Math. The findings were sobering: AI assessments fell short of aligning with human perceptions, with an average Spearman correlation score below 0.50. Notably, even the latest models like GPT-5 scored only 0.34, while the older GPT-4.1 fared slightly better at 0.44.

When the researchers aggregated the predictions from the 14 highest-performing models, they achieved a correlation of approximately 0.66 with human difficulty ratings. This still indicates only moderate agreement, highlighting a fundamental disconnect in how AI systems interpret question difficulty compared to actual human learners.

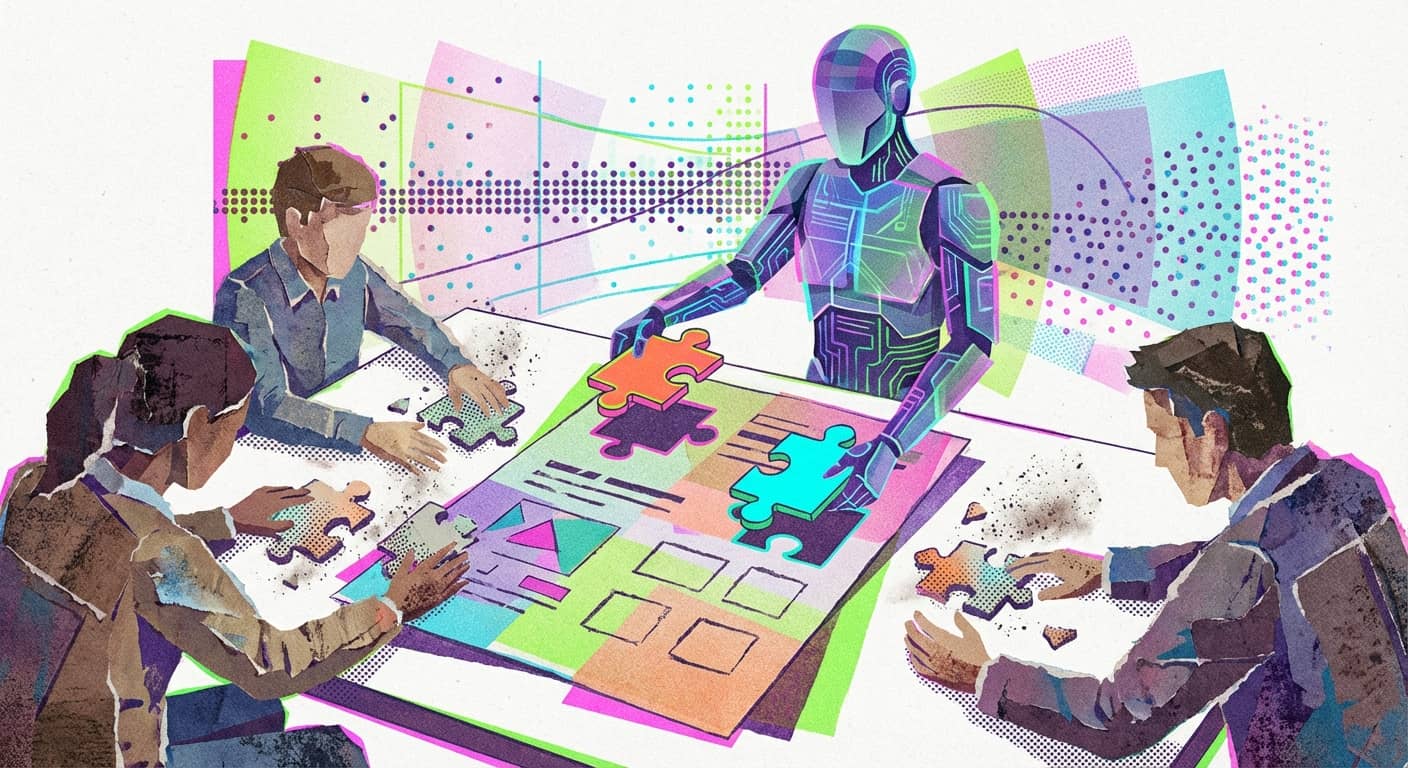

The study’s authors attribute this discrepancy to what they term the “curse of knowledge.” This phenomenon suggests that the advanced capabilities of LLMs prevent them from understanding the challenges faced by less skilled learners. For instance, while these models easily navigated tasks that frequently stumped medical students, they failed to recognize the specific hurdles that posed significant difficulties for human test-takers.

Attempts to mitigate this issue by prompting models to role-play as various types of learners yielded limited success. The models’ accuracy shifted by less than one percentage point regardless of whether they were instructed to simulate weak, average, or strong students. This lack of adaptability indicates that LLMs cannot scale down their own abilities to mimic the mistakes typical of less proficient learners.

Another critical finding revealed that when LLMs rated a question as difficult, they did not necessarily struggle with it. For example, GPT-5’s performance did not correlate with its difficulty estimates, demonstrating a lack of self-awareness regarding its limitations. The models’ assessments of difficulty and their actual performance appeared largely disconnected, leading the authors to suggest that these systems lack the self-reflection needed to recognize their own constraints.

Rather than approximating human perceptions, the LLMs developed a “machine consensus,” which diverged systematically from human data. This consensus often underestimated question difficulty, with model predictions clustering in a narrow range, whereas actual difficulty values exhibited a broader distribution. Previous research has similarly highlighted the tendency of AI models to form agreement, regardless of accuracy.

The implications of this study are significant for the future of AI in education. Accurately determining task difficulty is vital for educational testing, influencing curriculum design, automated test creation, and adaptive learning systems. Until now, the conventional approach has relied heavily on extensive field testing with actual students. Researchers had hoped that LLMs could assume this responsibility; however, the findings complicate that vision. Solving problems does not equate to understanding the reasons behind human struggles, suggesting that making AI effective in educational contexts will necessitate methods beyond simple prompting. One potential solution could involve training models using student error data to bridge the gap between machine capabilities and human learning.

OpenAI’s own usage data indicates the increasing role of AI in education, with “writing and editing” topping the list of popular use cases in Germany, closely followed by “tutoring and education.” Former OpenAI researcher Andrej Karpathy recently advocated for a radical transformation of the education system, suggesting that schools should assume any work completed outside the classroom involves AI assistance, given the unreliability of detection tools. Karpathy proposed a “flipped classroom” model, where exams occur at school and knowledge acquisition, supported by AI, takes place at home. His vision emphasizes the need for dual competence, enabling students to effectively collaborate with AI while also functioning independently of it.

See also ZhiZhi Innovation Launches IQuest-Coder V1, Surpassing 81.4% in Benchmark Tests

ZhiZhi Innovation Launches IQuest-Coder V1, Surpassing 81.4% in Benchmark Tests Invest in AI Now: Top 3 Stocks to Watch—Palantir, SoundHound, and Tesla

Invest in AI Now: Top 3 Stocks to Watch—Palantir, SoundHound, and Tesla Global Economic Outlook 2026: AI Bubble Risks, Fed Turmoil, and 15% Market Gains Predicted

Global Economic Outlook 2026: AI Bubble Risks, Fed Turmoil, and 15% Market Gains Predicted Meta Aims to Transform WhatsApp into a Global Super App by 2026, Predicts AI Experts

Meta Aims to Transform WhatsApp into a Global Super App by 2026, Predicts AI Experts AI Revolutionizes Daily Life in America: From Smart Homes to Healthcare Innovations

AI Revolutionizes Daily Life in America: From Smart Homes to Healthcare Innovations