Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Last week, the US Department of Energy unveiled 26 “science and technology challenges of national importance” to propel the Genesis Mission, an initiative aimed at accelerating scientific research through artificial intelligence (AI). This initiative is not merely about enhancing research velocity; it seeks to fundamentally transform how science is conceived, tested, and advanced, condensing years of discovery into mere weeks. As the speed of scientific inquiry accelerates, the balance of global power is also poised for change.

What was announced in Washington is not just another AI policy; it is a declaration recognizing that the pace of scientific discovery itself has become a strategic asset. This is a crucial point for New Delhi to consider as it prepares to host the AI Impact Summit in 2026. India must confront a challenging reality: its scientific infrastructure is largely rooted in a 20th-century model that limits the speed of discovery.

The Genesis Mission’s most radical concept is a straightforward one: scientific discovery can be expedited not solely through individual brilliance but through computation, automation, and integration. AI systems are expected to design experiments, optimize energy grids, digitize nuclear data, accelerate material discovery, and significantly reduce the trial-and-error process. The explicit goal is to make parts of scientific inquiry 20 to 100 times faster. Historically, nations competed based on the volume of discoveries; now, the competition will hinge on the speed of those discoveries. In this evolving landscape, nations that lag will not only fall behind but might also become increasingly dependent.

India’s existing scientific framework is not optimized for speed. Its research ecosystem is fragmented across various ministries, councils, autonomous institutes, public sector labs, and universities. Data standards remain inconsistent, and collaboration is often reliant on personal networks rather than shared infrastructure. Furthermore, funding cycles are slow, compliance-heavy, and cautious, stifling innovation.

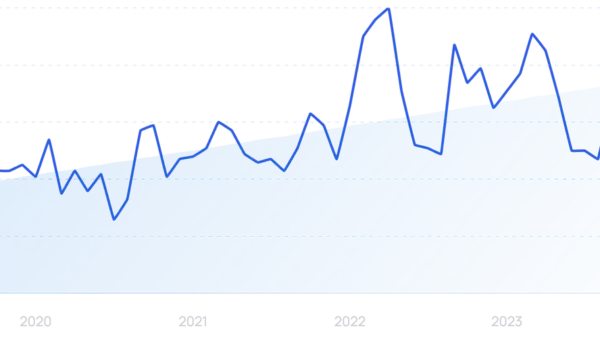

In the 2023-24 fiscal year, India’s total public R&D spending was approximately 0.65-0.7% of GDP, while China allocates around 2.4% and the US approximately 3.4%. More critically, a substantial portion of US R&D is focused on mission-oriented, high-performance computing, whereas India’s resources are dispersed thinly across thousands of institutions, many lacking digital capabilities.

While India discusses AI in governance, startups, ethics, policy, and skilling, it seldom regards AI as a fundamental component of its national scientific infrastructure, comparable to power grids or space launch facilities. The US Genesis Mission embodies this integration, blending supercomputers, national labs, datasets, sensors, experimental facilities, and AI models into a cohesive discovery ecosystem. This initiative transcends traditional applications; it is fundamentally about infusing intelligence into the physical sciences.

As AI systems trained on extensive national data begin generating proposals for new materials, reactor designs, or quantum algorithms, the very concept of sovereignty is shifting. It is moving from traditional labs into models, computing, and data governance. This is precisely why the Genesis Mission is situated within the Department of Energy, rather than at a university consortium; it recognizes energy, defense, discovery, and AI as a unified strategic continuum.

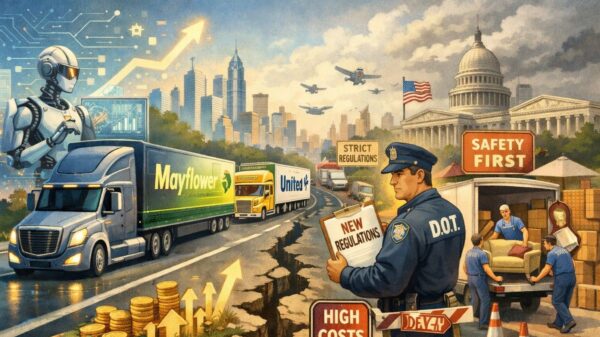

India has extensive collaborations with global research networks, which represents a strength. However, without developing its own AI and scientific capabilities, it risks creating a new asymmetry: India could become a supplier of talent and data, while others control the engines of discovery. A particularly disruptive aspect of the Genesis initiative is its push toward autonomous labs—systems where experiments are conducted, adjusted, and refined by machines with minimal human oversight. This paradigm shift necessitates advanced robotics, high-quality sensors, real-time data pipelines, standards for reproducibility, and significant computing power.

Across Indian universities and public research institutions, data is frequently stored in incompatible formats, experimental protocols vary tremendously, and digitization efforts are sporadic. Many laboratories struggle with basic equipment reliability, let alone achieving autonomy. Before debating whether autonomous labs pose a threat to jobs or creativity, it is essential to address whether India’s scientific institutions are capable of being machine-readable.

There is also a notable irony in India’s AI aspirations. The energy consumption associated with AI acceleration is substantial. Large-scale AI models, supercomputers, and autonomous labs require reliable and high-capacity power. The US has explicitly anchored its AI-science strategy in energy planning, recognizing the interconnectedness of these domains—something India has yet to do.

India’s peak power demand surpassed 250 GW in 2024, with recurring shortages reported in several states. Data centers currently consume about 3-4% of the nation’s electricity—a figure expected to rise significantly. However, discussions about AI strategies and energy planning rarely overlap. It is impractical to establish an AI-driven scientific economy on an energy system outdated for contemporary demands.

The Genesis initiative compels a reevaluation of scientific education as well. If AI systems increasingly take on the roles of designing experiments and analyzing data, what will a scientist trained strictly in traditional methodologies become by 2035? India produces a vast number of science graduates, but its curricula often lag behind current practices by a decade or more. Systems thinking, computation-first experimentation, and AI-guided modeling remain peripheral to many educational institutions.

Without significant reform, India risks cultivating highly skilled scientists for a world that may no longer exist. While India does not need to replicate the US Genesis Mission, it faces different priorities and constraints that are equally pressing. Ignoring the strategic shift represented by such initiatives would be a critical oversight. India must engage in a national discourse on three fundamental questions: Should it develop an AI-science platform to connect institutions into a shared computational and data backbone? How can it ensure scientific sovereignty in an era when discovery is driven by AI trained on national data? Is its funding, institutional design, and educational framework ready for the demands of machine-accelerated science?

The US has made a decisive choice that the future of science will be characterized by speed, with that speed becoming a weapon in global competition. India now has the option to respond proactively or risk continuing its current trajectory while others advance.