Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a vital battleground for global political conflicts, transcending its initial discussions surrounding innovation and efficiency. In an age when governments are increasingly framing the discourse around “AI sovereignty” and “data sovereignty,” the stakes have escalated to levels once reserved for territorial and energy security. This shift was evident at the European Digital Sovereignty summit in November 2025, which brought together approximately 900 policymakers and industry leaders in a bid to address these challenges, yet failed to yield substantial initiatives.

The essence of AI sovereignty, however, is fraught with contradictions, as many experts believe it is fundamentally impossible to achieve. Despite this, nations continue to view control over data, algorithms, and computing infrastructure as pivotal to enhancing their global influence. This competition has given rise to critical concerns: as countries strive to secure their technological futures, are they inadvertently undermining the global cooperation necessary for long-term benefits associated with AI?

The prospect of a fragmented AI landscape is no longer theoretical. Evidence of diverging technology blocs is already apparent, characterized by export controls on advanced chips, restrictions on cross-border data flows, and varying regulatory frameworks for “trustworthy AI.” These shifts threaten to create structural divides akin to the fragmentation observed in global internet governance, wherein incompatible technical, legal, and ethical frameworks may proliferate.

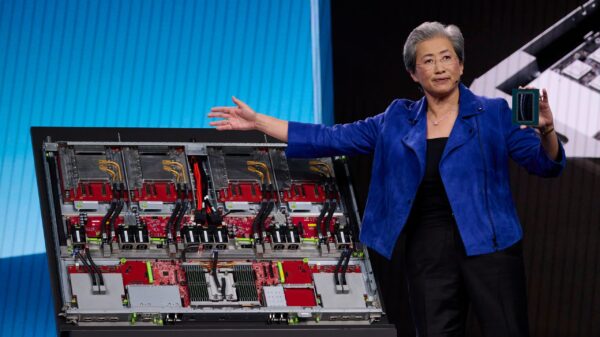

Several factors contribute to this fragmentation. AI systems are dual-use technologies crucial not only for economic competitiveness but also for military and intelligence capabilities. Nations often feel justified in reinforcing their technological defenses, fearing that reliance on foreign AI infrastructure or datasets could result in strategic vulnerabilities. In response, countries are increasingly investing in data localization, national cloud infrastructure, and domestic large language models as part of broader sovereignty projects.

This trend is evident in China’s focus on secure data governance, the European Union’s regulatory push for “digital sovereignty,” and the United States’ export controls aimed at maintaining its technological edge. Collectively, these measures signal a consensus that AI must not be left to the whims of the global market.

However, a world divided into competing AI blocs could lead to inefficiencies and greater risks. AI systems inherently transcend borders: models trained in one nation can be deployed in another, and datasets are increasingly sourced from around the globe. Problems such as algorithmic bias and misinformation are not confined to national boundaries, meaning that fragmentation would likely complicate governance rather than mitigate risks.

The pressing challenge lies in finding a balance between national interests and international cooperation. While it is reasonable for nations to assert control over critical infrastructure or sensitive datasets, the rationale for fragmenting cooperative efforts in areas like AI safety research or standards for robustness and interoperability is less clear. These domains are crucial for collective interests.

Global AI safety summits highlight the potential of collaboration while revealing its limitations. Although these forums recognize shared risks, such as the loss of human control over AI systems, they remain largely voluntary and politically cautious. The challenge of transforming declarations into actionable institutions remains significant.

Existing global governance structures are ill-equipped to address the pace of AI development. Traditional treaty-making is sluggish, while AI progresses rapidly, and many international organizations lack the requisite technical expertise or political backing. Additionally, standard-setting bodies, which play a critical role in governance, are often dominated by a select few countries and companies, perpetuating perceptions of inequality.

Geopolitical mistrust further complicates the landscape. In an environment defined by strategic rivalry, cooperation can be perceived as a concession, with transparency treated as a potential risk. Even fundamental measures, such as sharing information about potent AI models or establishing common definitions of systemic risks, can quickly become contentious.

In this context, a Chinese proverb offers a relevant perspective: “Lookers-on see more than players.” While diplomats and policymakers may be grappling with complexities, academics and AI experts are positioned to guide discussions, pinpoint risks, and propose pathways forward that protect rights while fostering innovation.

History illustrates that sovereignty and cooperation are not mutually exclusive. Successful arms control regimes, environmental treaties, and global trade rules emerged during periods of intense competition, not by abandoning sovereignty but by recognizing that uncoordinated actions would ultimately harm all parties. Cooperation thus becomes an exercise of sovereignty rather than its antithesis.

AI governance is ripe for a similar reframing. The focus should shift from “Who controls AI?” to “What aspects of AI necessitate shared rules to avert collective harm?” and “Which systemic risks warrant collaborative mitigation efforts?” This strategic pivot allows for diversity in values and systems while grounding cooperation in mutual precaution. For major AI players like China, this moment presents an opportunity; leadership in AI governance is increasingly about institutional creativity and the ability to bridge divides rather than deepen them.

See also Ireland Emerges as Top AI Investment Hub with 800 New Jobs from IBM and $202.5M Workday Boost

Ireland Emerges as Top AI Investment Hub with 800 New Jobs from IBM and $202.5M Workday Boost Top AI Books for 2026: Insights from Tom Fox on Key Titles for Professionals

Top AI Books for 2026: Insights from Tom Fox on Key Titles for Professionals Indonesia Proposes Draft Regulation to Govern AI Use in Criminal Justice System

Indonesia Proposes Draft Regulation to Govern AI Use in Criminal Justice System Arhasi Introduces R.A.P.I.D. Framework to Scale AI with Trust and Orchestration

Arhasi Introduces R.A.P.I.D. Framework to Scale AI with Trust and Orchestration