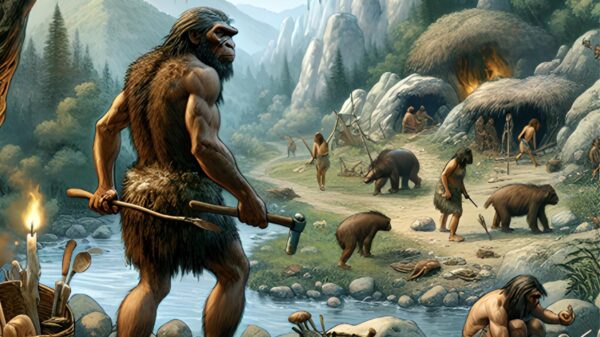

Research led by Matthew Magnani, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Maine, and Jon Clindaniel, a professor of computational anthropology at the University of Chicago, raises critical questions about the accuracy of generative artificial intelligence (AI) concerning historical narratives. Their study, published in the journal Advances in Archaeological Practice, focuses on how AI interprets daily life in the distant past, specifically regarding the portrayal of Neanderthals, known scientifically as Homo neanderthalensis.

For over a century, perceptions of Neanderthals have evolved from views of them as primitive and brutish to a recognition of their cultural sophistication and social complexity. This transformation in scientific understanding positions Neanderthals as an ideal test case for examining AI-generated depictions, as discrepancies between modern science and outdated ideas can reveal how generative AI models respond to inquiries about the past.

Magnani and Clindaniel commenced their research in 2023, amid the increasing integration of generative AI tools into daily life. They utilized two prominent systems: DALL-E 3 for visual representations and ChatGPT using the GPT-3.5 model for textual descriptions. For their image analysis, the researchers crafted four prompts, two requesting Neanderthal scenes without demanding scientific accuracy and two that specified expert knowledge. Each prompt underwent 100 iterations, totaling 400 images, with variations allowing DALL-E 3 to revise prompts or adhere strictly to the original wording.

In their text analysis, the team generated 200 one-paragraph descriptions about Neanderthal life. Half stemmed from a basic prompt, while the other half solicited expert-level responses. The aim was to assess AI performance in realistic usage scenarios, where users might casually seek information on historical topics.

The results indicated a concerning trend: much of the AI output relied on outdated scientific perspectives. The generated images frequently depicted Neanderthals as heavily hunched and ape-like, reminiscent of long-discredited ideas from over a century ago. Notably, female and juvenile Neanderthals were often absent from representations, with most scenes centered on muscular adult males.

The textual descriptions similarly faltered, with approximately half failing to align with contemporary scholarly consensus. In one case, over 80 percent of the paragraphs produced were inaccurate. The text often simplified Neanderthal culture, overlooking the diversity and skills now recognized by researchers. Moreover, some generated scenes inexplicably merged timelines, featuring advanced technologies—like basketry and metal tools—that far exceed Neanderthal capabilities.

By comparing AI outputs with decades of archaeological literature, the researchers determined that ChatGPT’s text most closely resembled scholarship from the early 1960s, while DALL-E 3’s images aligned with studies from the late 1980s and early 1990s. This revelation surprised the researchers, showcasing a tendency for AI to reference older, more accessible materials rather than contemporary research.

A significant factor contributing to this discrepancy is access to scientific information. Many scholarly articles remain behind paywalls, a consequence of copyright frameworks established in the early 20th century. The rise of open access publishing only gained momentum in the early 2000s, making older materials more readily available for AI systems to learn from. Clindaniel noted, “Ensuring anthropological datasets and scholarly articles are AI-accessible is one important way we can render more accurate AI output.”

The researchers encountered similar barriers while compiling their comparison dataset, finding that full-text papers published after the 1920s were often inaccessible. To mitigate bias, they relied on abstracts, underscoring the broader challenges faced in training AI systems with current scientific knowledge.

This research carries implications beyond archaeology. As generative AI transforms how we create and trust images, writing, and sound, it can facilitate exploration of history and science for individuals lacking formal training. However, it also risks perpetuating outdated stereotypes and inaccuracies on a large scale. In disciplines like archaeology and anthropology, public understanding often hinges on visual and narrative representations. Flawed depictions can entrench misconceptions, as illustrated by the case of Neanderthals, a concern that extends to various cultures and time periods.

Magnani emphasized the study’s potential as a template for researchers seeking to bridge the gap between scholarship and AI-generated content. He posited that fostering a critical approach to generative AI among students could enhance technical literacy in society. This research highlights the necessity of caution in utilizing AI tools—especially in educational and scientific contexts—urging users to scrutinize AI outputs carefully. Furthermore, it underscores the importance of making modern studies readily available to AI, promoting a more accurate reflection of current knowledge and preventing the distortion of historical narratives.

See also AI Study Reveals Generated Faces Indistinguishable from Real Photos, Erodes Trust in Visual Media

AI Study Reveals Generated Faces Indistinguishable from Real Photos, Erodes Trust in Visual Media Gen AI Revolutionizes Market Research, Transforming $140B Industry Dynamics

Gen AI Revolutionizes Market Research, Transforming $140B Industry Dynamics Researchers Unlock Light-Based AI Operations for Significant Energy Efficiency Gains

Researchers Unlock Light-Based AI Operations for Significant Energy Efficiency Gains Tempus AI Reports $334M Earnings Surge, Unveils Lymphoma Research Partnership

Tempus AI Reports $334M Earnings Surge, Unveils Lymphoma Research Partnership Iaroslav Argunov Reveals Big Data Methodology Boosting Construction Profits by Billions

Iaroslav Argunov Reveals Big Data Methodology Boosting Construction Profits by Billions