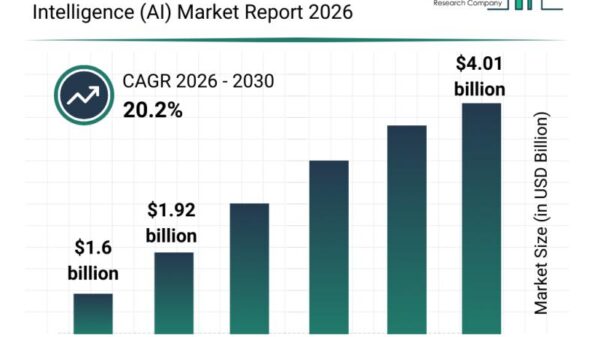

OpenAI’s recent commitment of $1.4 trillion to secure future computing capacity underscores the mounting excitement surrounding AI investments in 2025. This influx of capital comes amid reports suggesting that U.S. GDP growth in the first half of this year has been largely driven by the expansion of data centers. Such trends have led to increased speculation regarding a potential bubble in the AI sector, reminiscent of the dot-com era. However, the current landscape differs significantly, with gains appearing more muted and macroeconomic challenges more pronounced than in previous technology booms.

During the late 1990s, the internet-driven economic boom was characterized by rapid labor productivity growth, averaging about 2.8 percent from 1995 to 2004. Although U.S. labor productivity growth rose to about 2.7 percent last year, it remains uncertain whether AI adoption is a key factor. Notably, AI adoption rates appear to be declining. If the recent productivity uptick is indeed driven by AI, there is a risk that this momentum could dissipate as adoption wanes, echoing the transient nature of previous technological waves.

Challenges Ahead

The allure of large language models (LLMs) as catalysts for innovation—by uncovering hidden connections in academic literature and automating coding tasks—can be irresistible. Historical advancements, from Robert Hooke’s microscope to Galileo’s telescope, have repeatedly accelerated discoveries. Yet, the pervasive availability of knowledge via internet-connected PCs has not necessarily translated to increased research productivity or breakthrough innovations, which have seen a decline despite improved access to information.

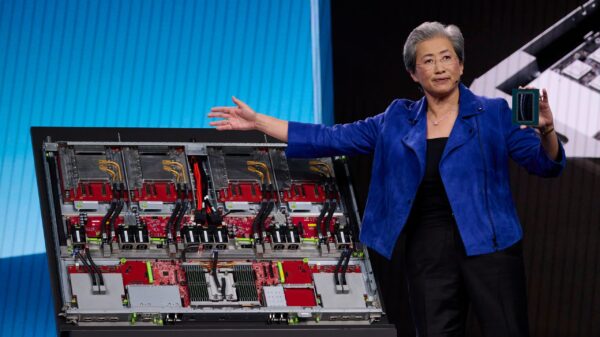

Furthermore, the current surge in capital expenditures may not yield lasting digital infrastructure benefits. Unlike the 19th-century railroad investments, which laid the groundwork for long-lasting assets, the AI sector’s rapid technological advancements lead to frequent obsolescence. For example, training an LLM now necessitates around 120 kilowatts of power—an increase from 5-10 kW just a decade ago. This pattern of rapid technological change necessitates constant reinvestment, as server racks and chips quickly become outdated.

In contrast to the favorable macroeconomic conditions of the late 1990s, today’s landscape presents significant hurdles. During that period, a budget surplus and declining debt-to-GDP ratio provided a supportive environment for capital markets. Currently, persistent U.S. government deficits—hovering around 6 percent of GDP—and net interest payments nearing $1 trillion create fiscal constraints that could impact AI funding. This increased demand from multiple sectors, including clean energy and defense, has raised borrowing costs, potentially stifling new housing projects and delaying substantial infrastructure undertakings.

Systemic Risks and Market Dynamics

Public finances are also under strain, as a larger debt stock means higher interest payments, which can crowd out essential government programs. In the late 1990s, the falling debt allowed for a collaborative investment climate alongside private sector growth. Today, however, the need for additional borrowing and a heavier interest burden limit the government’s maneuverability, particularly if economic growth falters. Should AI’s promised benefits materialize slowly, the fiscal implications could exacerbate existing pressures, leading to tougher trade-offs between funding for social services and obligations to bondholders.

Additionally, the financing landscape differs significantly from the dot-com era. The downturn of the early 2000s was primarily an equity concern, with stock prices suffering a collapse but lacking systemic risk due to limited impact on banks’ balance sheets. In contrast, today’s credit-driven build-out could introduce systemic risks, as funding transitions from equity to bonds and private credit—financial instruments that are inherently tied to banks and insurers. Should AI and data-center revenues fall short of expectations, the ramifications are likely to emerge first in credit markets, leading to tighter loan terms and potential refinancing challenges for lenders.

As noted by investor Paul Kedrosky, the current financial architecture heightens the possibility of stress spreading through financial institutions and structured vehicles due to AI investments. If rapid and sustained productivity gains emerge from AI advancements, the macroeconomic outlook could improve, easing fiscal pressure and improving debt ratios. However, if the anticipated benefits are delayed or fail to meet projections, the substantial upfront costs may outweigh the eventual payoffs.

The author is the director of the Future of Work Programme at the Oxford Martin School.

– Project Syndicate

See also Google DeepMind’s Lila Ibrahim Reveals Strategies for Global AI Accessibility

Google DeepMind’s Lila Ibrahim Reveals Strategies for Global AI Accessibility Raymond James Upgrades Doximity: AI-Focused Growth Potential Sparks Investor Interest

Raymond James Upgrades Doximity: AI-Focused Growth Potential Sparks Investor Interest vLLM, TensorRT-LLM, TGI v3, and LMDeploy: A Technical Breakdown of LLM Inference Performance

vLLM, TensorRT-LLM, TGI v3, and LMDeploy: A Technical Breakdown of LLM Inference Performance Zeta Global’s AI-Driven Athena Launch Fuels Revenue Growth Outlook Despite Losses

Zeta Global’s AI-Driven Athena Launch Fuels Revenue Growth Outlook Despite Losses Perplexity Tests New AI Model C Amid Speculation on Claude 4.5 Launch

Perplexity Tests New AI Model C Amid Speculation on Claude 4.5 Launch