AI’s Governance Challenges in Financial Institutions

Artificial intelligence (AI) is exposing the tendency of institutions to prioritize form over substance, raising critical questions about productivity and decision-making in finance. As AI tools enhance output, they often obscure a deeper understanding of the underlying processes, creating governance challenges that regulators may scrutinize when decisions affect client outcomes.

Reflecting on the late 1990s and the Y2K debate, financial institutions grappled with the fear of system failures, prompting a wave of declarations from asset managers about their readiness. However, when January 1, 2000, arrived without incident, it became clear that reliance on paperwork could not replace genuine preparedness. This historical context highlights a troubling parallel with today’s discussions around AI—where institutions often focus on the volume of output rather than the depth of understanding that is crucial for sound decision-making.

The implementation of large language models (LLMs) exemplifies this duality. A skilled analyst can leverage these tools to refine questions and focus on complex tasks, while a less experienced user may produce extensive but superficial content lacking in comprehension. The gap between volume and understanding poses significant risks, particularly in compliance and risk management scenarios, where decisions impact member balances and client trajectories.

As seen in the evolution of the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) program, the introduction of technology like the HP-12C calculator was not seen as a dilution of standards, but rather a recognition of practical realities in the profession. The focus shifted from manual computation to critical judgment, emphasizing that human oversight remained essential even in the presence of advanced tools. The same principle applies to AI; while it can generate reports and streamline client interactions, the crucial factor is whether those using the technology can interpret and analyze the outputs meaningfully.

Economists often cite William Jevons, who noted that increased efficiency typically results in higher demand rather than a reduction in it. This phenomenon is evident in the field of radiology, where AI-assisted tools have elevated scan volumes and, consequently, the demand for trained professionals. Similarly, in finance, AI can drive up the quantity of reports generated and client communications, but the central concern remains: does understanding keep pace with this increased output?

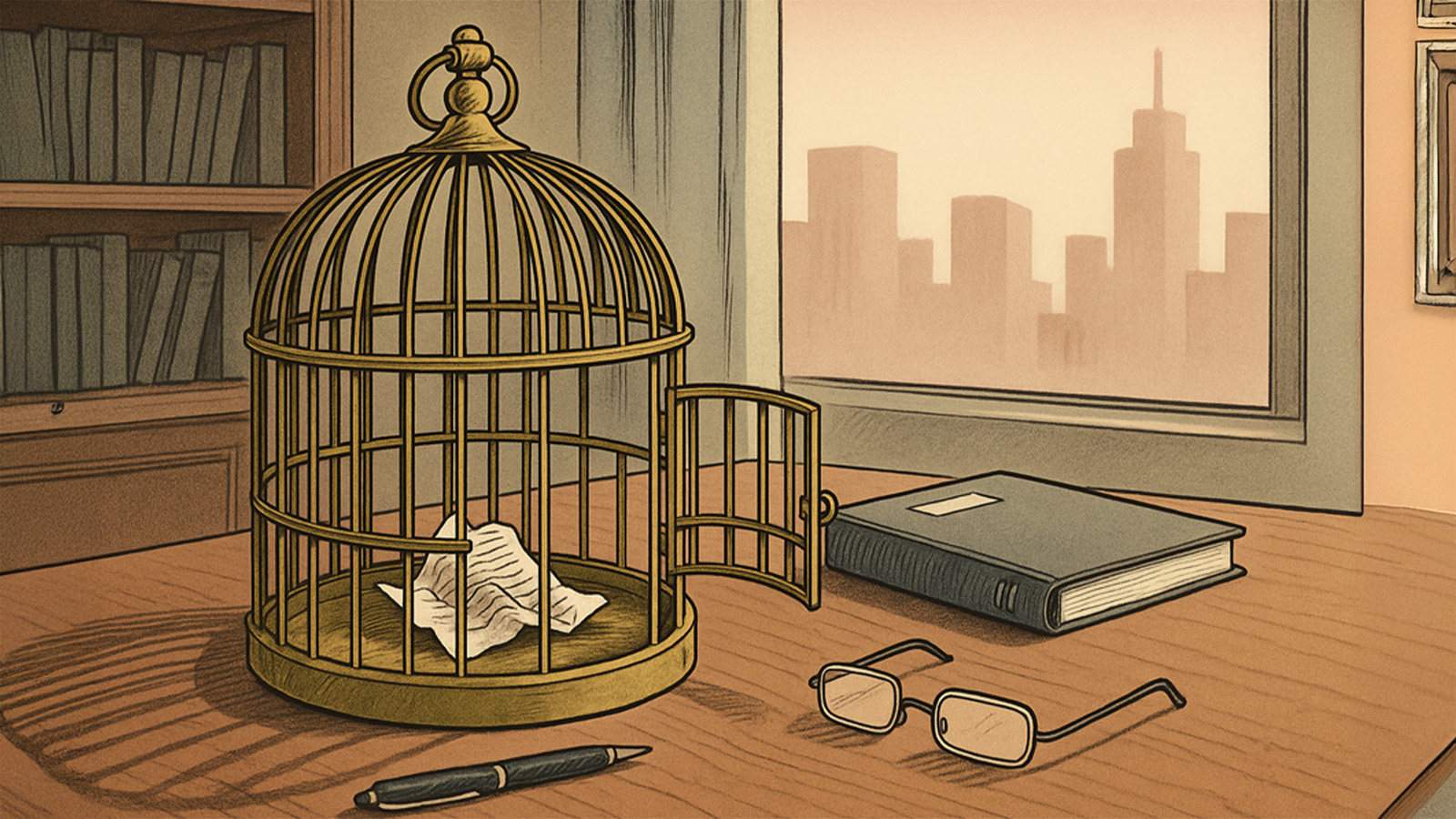

The governance frameworks within financial institutions may falter when faced with the complexities introduced by AI. As organizations adopt AI technologies to enhance performance metrics—such as reducing headcounts and accelerating processes—a disconnect can emerge between what is produced and the accountability behind those outputs. Instances have occurred where companies cut roles based on AI promises, only to rehire staff when operational shortcomings became evident. The failure, in these cases, was not the technology but rather the delegation of critical judgment.

For board members, navigating two learning curves is imperative: one focused on the technical aspects of AI architectures and model selection, and the other on governance principles that dictate decision-making authority and accountability. The alignment of incentives with responsibilities is paramount, as the repercussions of missteps in these domains can lead to substantial fiduciary risks.

Data governance also plays a crucial role in the efficacy of AI systems. The emergence of “hallucinations,” where AI generates plausible but factually incorrect statements, underscores the importance of robust data management practices. Institutions must ensure a clear lineage of data sources, encompassing consent and ownership rights, to bolster the integrity of AI-driven decisions. The pressure is on boards to apply the same rigor to AI initiatives as they do to traditional risk management practices, ensuring that success is measured through tangible client outcomes.

As the landscape of AI continues to evolve, the infrastructure supporting these technologies will also require scrutiny. Fluctuations in energy prices and resource availability may introduce new cost structures that impact overall project viability. Institutions need to remain cognizant of these dynamics, as they will shape who ultimately bears the financial burden when AI utility does not meet expectations.

Ultimately, the challenge for financial institutions lies not in the adoption of AI but in the manner in which they integrate these tools into their governance frameworks. AI does not eliminate the necessity for human judgment; rather, it reveals areas where such judgment has been lacking. As organizations navigate this evolving landscape, those that prioritize thorough governance and accountability will possess a distinct advantage in an increasingly complex financial environment. The code may be new, but the responsibility for sound decision-making remains unchanged.

Rob Prugue

See also Google Cloud’s PanyaThAI Initiative Targets 15 Thai Firms, Aims for $21B AI Impact by 2030

Google Cloud’s PanyaThAI Initiative Targets 15 Thai Firms, Aims for $21B AI Impact by 2030 Cyber Resilience and AI Integration: Key Trends Shaping IT Strategies for 2026

Cyber Resilience and AI Integration: Key Trends Shaping IT Strategies for 2026 OpenAI and Apollo Research Reveal Alarming Signs of “Scheming” in AI Models

OpenAI and Apollo Research Reveal Alarming Signs of “Scheming” in AI Models Google’s Gemini 3 Surpasses ChatGPT, Reclaims AI Leadership with $112B in Cash Reserves

Google’s Gemini 3 Surpasses ChatGPT, Reclaims AI Leadership with $112B in Cash Reserves