SINCE ChatGPT burst onto the scene in late 2022, the global labour market has been haunted by a singular spectre: replacement anxiety. The narrative is familiar: generative artificial intelligence (AI) will automate white-collar drudgery, rendering accountants, copywriters, and coders obsolete. However, three years into this technological revolution, the data suggests that AI does not treat all economies equally. By comparing the labour markets of China and Singapore, we find two radically different paths: one where technology acts as a harsh filter replacing workers, and another where it fosters resilience through integration.

While the US labour market is often the primary focus of empirical analysis, Asian economies offer a unique comparative laboratory due to their distinct institutional environments and industrial structures. Our research draws on a massive dataset comprising millions of recruitment ads from major Chinese platforms and a comprehensive set of 15 million job postings in Singapore, covering nearly every employer in the city-state from 2012 to October 2025.

In China, the arrival of large language models (LLMs) has indeed functioned as a blunt instrument of displacement. Our analysis of the Chinese market reveals that white-collar professions with high “exposure” to AI, such as accounting, editing, and sales, suffered a distinct contraction in recruitment demand following the proliferation of generative AI. In this context, technology serves as a rigorous filter: it accelerates the elimination of highly routine tasks and raises the barrier to entry.

For high-exposure roles in China, employers have responded not by hiring more tech-savvy juniors but by demanding significantly higher educational qualifications and experience levels, effectively squeezing out the middle tier of the workforce. Notably, the “AI-LLM Exposure Index” for new postings in China dropped significantly after 2023. This is not a sign of reduced technological relevance; rather, it suggests that many jobs susceptible to automation were simply “cleared out” of the market entirely.

However, Singapore, with its service-heavy economy, high digitalisation, and concentration of multinational headquarters, tells a different story. Despite the rapid evolution of AI, Singapore’s labour market has shown remarkable structural stability. Unlike China, the AI exposure index for new jobs in Singapore has remained high and steady. The market did not shed these “exposed” jobs; it absorbed the shock.

Why the divergence? The answer lies in how companies are deploying the technology. In Singapore, we observed a distinct shift in the type of AI talent sought by companies, moving from “builders” to “integrators.” Between 2018 and 2021, demand for AI talent in Singapore was dominated by what we call “Deep AI” roles, research scientists, and algorithm engineers building models from scratch. This demand cooled in 2022. But starting in early 2023, a new structural trend emerged: a surge in demand for “AI Users” and, crucially, “AI Integrators.”

AI Integrators are not necessarily machine-learning PhDs. They are professionals tasked with embedding existing models into business workflows via APIs, fine-tuning, or Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). By late 2025, the proportion of Singaporean firms hiring for these integration roles had climbed significantly. These companies are not trying to replace humans with chatbots; they are re-engineering their operations to make humans more productive using AI.

This distinction, between replacement and integration, is the key to navigating the AI age. Singapore’s experience demonstrates that high AI exposure does not have to lead to mass unemployment. When technology transitions from a tool for cost-cutting substitution to a mechanism for business integration, it creates new employment spacing.

For economies facing the “replacement anxiety” visible in China, the policy imperative is clear. First, the focus must shift from merely developing foundation models to building an application ecosystem. We need more roles focused on the “how” of business application rather than just the “what” of model architecture.

Second, workforce training must pivot. The era of memorising fixed knowledge is over; the value now lies in the ability to command AI to solve complex problems and manage uncertainty. The divergence between China and Singapore serves as a warning and a blueprint. If AI is treated solely as a substitute for labour, it will indeed act as a harsh filter. But if it is treated as an organisational capability to be integrated, it becomes a catalyst for resilience. The machines are here, but the choice of how to employ them remains distinctly human.

Nvidia, OpenAI, and other tech innovators must focus not only on the power of AI but also on its role within human workflows, ensuring that economies can adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing landscape.

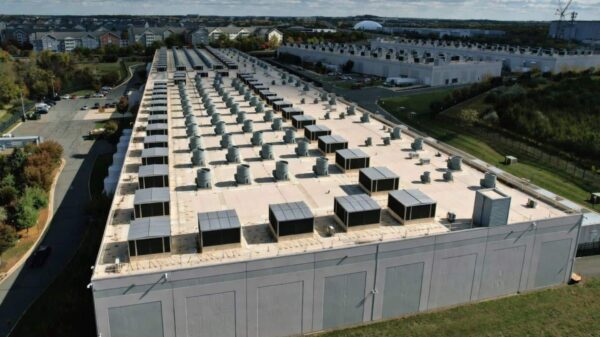

See also Meta Secures Nuclear Power Deals with TerraPower, Oklo, and Vistra for AI Data Centers

Meta Secures Nuclear Power Deals with TerraPower, Oklo, and Vistra for AI Data Centers Markets Face Heightened Volatility as U.S. Policy, AI Regulation, and Geopolitical Tensions Intensify

Markets Face Heightened Volatility as U.S. Policy, AI Regulation, and Geopolitical Tensions Intensify Agentic Discovery Hackathon to Propel Autonomous AI’s Role in Scientific Research

Agentic Discovery Hackathon to Propel Autonomous AI’s Role in Scientific Research Anthropic Seeks $10B in Funding as AI Bubble Concerns Rise Among Experts

Anthropic Seeks $10B in Funding as AI Bubble Concerns Rise Among Experts