Baltimore’s ongoing efforts to enhance school safety have led to the adoption of AI-driven technologies, garnering both attention and concern. Recently, a second Maryland school system has implemented the controversial Omnilert AI weapons detection software, which has faced scrutiny regarding its effectiveness and reliability.

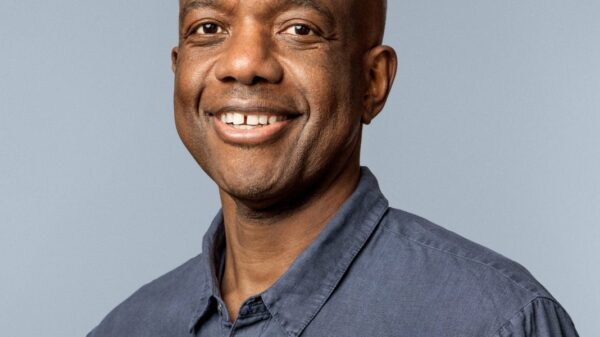

The Maryland Fraternal Order of Police President, Sergeant Clyde Boatwright, has expressed skepticism about the technology, stating, “I think that it (AI weapons detection software) is flawed. There’s a difference between feeling safe and actually being safe.” His comments reflect growing unease among law enforcement officials about the capabilities of AI in critical safety scenarios.

Omnilert, which has been in use in several Maryland schools, has not proven itself in high-stakes situations. Earlier this year, during a tragic school shooting in Tennessee, the software failed to notify authorities that a gun had been fired. According to Sean Braisted, a spokesperson for Nashville Schools, the system did not activate due to the shooter’s position and the weapon’s location.

In a different incident in Baltimore County, Omnilert mistakenly identified a bag of chips as a firearm, leading to the detention of a teenager. This incident, alongside Omnilert’s $2.6 million contract with Baltimore County Public Schools for four years, has raised questions among taxpayers about the efficacy of a system that has yet to demonstrate a successful interception of an actual threat.

Now, Charles County Public Schools has also engaged Omnilert, further intensifying concerns. A recent safety report from the school district detailed an incident on April 10 when a firearm was brought to Billingsley Elementary School for three consecutive days without detection by the software. The report indicated that the technology only identifies visible firearms, leaving concealed weapons undetected. “If a person has a handgun and it’s concealed, you’re not going to be able to see that until they produce the handgun,” Boatwright noted, emphasizing the limitations of AI technology in ensuring safety.

Despite the significant financial commitment from taxpayers, both Charles County and Baltimore County school districts have been reticent about providing examples of Omnilert’s successful interventions. When Project Baltimore inquired about instances where the software functioned as intended, both districts declined to share specific examples, raising additional concerns about transparency and accountability.

As the debate continues, Boatwright stressed, “When we’re talking about safety of young people and getting it right every time, we have to get it right, each time.” His argument underscores the critical nature of traditional security measures, such as metal detectors and the presence of security officers, which have a proven track record in school safety.

In light of its shortcomings, the integration of Omnilert raises pressing questions about the accountability in cases of failure. Boatwright articulated this concern, stating, “If there is a tragedy at a school, I don’t know who would be held accountable if it’s the artificial intelligence that fails.”

Omnilert maintains that its system was not responsible for the Tennessee incident, citing that the cameras did not capture the shooting. As Project Baltimore continues its investigation, they are in communication with Omnilert to schedule an in-person demonstration of the product’s intended functionalities.

The growing reliance on AI technologies in safety-critical environments necessitates a thorough evaluation of their effectiveness. As AI systems like Omnilert become more integrated into school safety strategies, the emphasis must remain on ensuring that these technologies are not only innovative but also reliable in protecting our youth.

See also Google Launches AI-Powered Travel Search with Visual Itineraries and Autonomous Booking

Google Launches AI-Powered Travel Search with Visual Itineraries and Autonomous Booking Bezos’ Project Prometheus Aims to Transform Manufacturing AI Alignment Challenges

Bezos’ Project Prometheus Aims to Transform Manufacturing AI Alignment Challenges Google Launches WeatherNext 2 AI, Delivers 8x Faster and More Accurate Forecasts

Google Launches WeatherNext 2 AI, Delivers 8x Faster and More Accurate Forecasts xAI Launches Grok 4.1 with 64% Preference for Enhanced Speed and Quality

xAI Launches Grok 4.1 with 64% Preference for Enhanced Speed and Quality