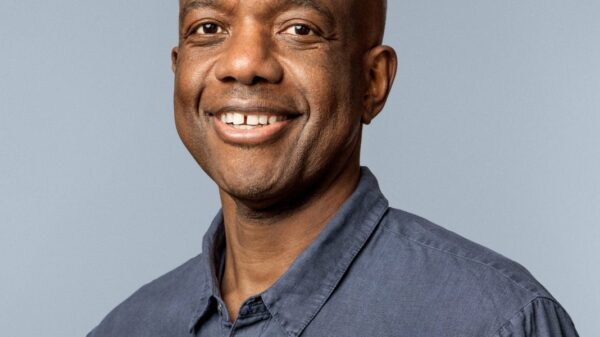

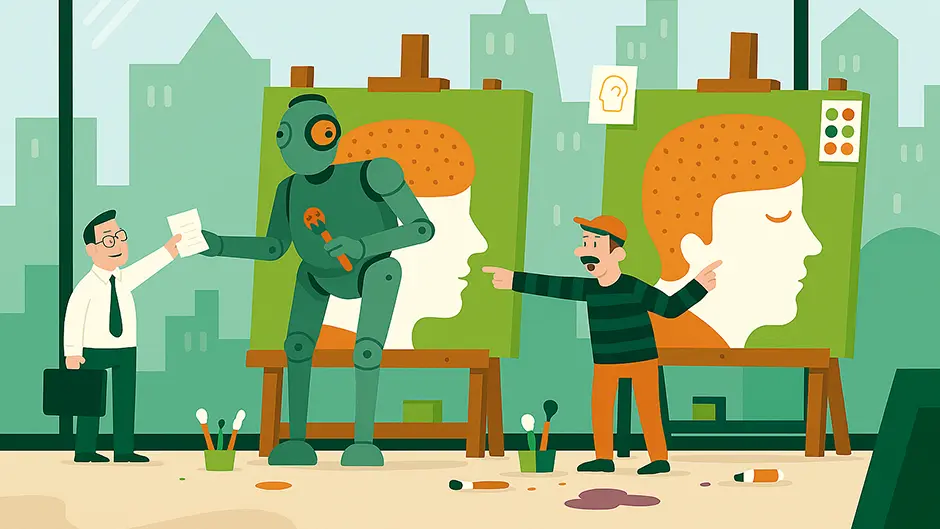

Recent research has highlighted a troubling trend in how people perceive copyright infringement in relation to artificial intelligence (AI). Individuals tend to assign greater culpability to works allegedly created by AI compared to those created by humans. This finding is part of a study co-authored by Joseph Avery, an assistant professor at the University of Miami’s Patti and Allan Herbert Business School, and Mike Schuster, an associate professor at the University of Georgia. The study, titled “AI Artists on the Stand: Bias Against Artificial Intelligence-Generated Works in Copyright Law,” is the first of its kind to explore how AI’s involvement can skew legal outcomes in copyright infringement cases.

Published in the UC Irvine Law Review, the study reveals a significant perceptual bias that emerges when evaluating creative works. “If a human and an AI do the exact same thing, with the same input and output, people still react differently,” Avery stated. This bias suggests that the invisible nature of the creative process influences the visible product, leading to harsher judgments against AI-generated works. This phenomenon has been termed the “AI litigation penalty,” where jurors and others involved in legal assessments impose greater penalties on works created by AI.

The empirical study involved participants viewing an original copyrighted piece and two identical works that were allegedly infringing—one attributed to a human creator and the other to AI. The results were striking: participants rated the AI-generated work as less ethical, fair, and of lower quality. In mock jury scenarios, they judged the AI-created work as significantly more infringing than its human-created counterpart. “People are consistently tougher when an AI is involved,” Avery noted, emphasizing that greater damages were often suggested for AI-generated works.

This litigation penalty is not confined to copyright issues alone. Avery’s forthcoming research indicates that similar biases may also be evident in patent and trade secret disputes, suggesting a broader systemic issue within legal frameworks. The reasons behind this perceptual bias and the resulting legal consequences remain a focal point of Avery’s ongoing research. “Perhaps we want to reward what feels human, and sometimes that instinct gets tangled up in our legal judgments,” he explained. “I suspect there are manifold reasons, and I plan on discovering them.”

The implications of this study extend beyond the realm of copyright law. Avery warns that this bias could serve as a cautionary tale for artists utilizing AI and the companies that employ them. He argues that if the legal system begins to penalize creative works solely based on the involvement of AI, it could undermine the fundamental purpose of copyright law. “The point of copyright is to encourage production and dissemination of creative works,” he said. “If we start punishing works simply because AI was part of the process, we may risk chilling innovation and limiting what people can imagine.”

As the capabilities of AI continue to evolve rapidly, Avery speculates that public perceptions may shift as well. “As we get used to AI, our reactions could flip,” he suggested, hinting at the potential for a change in how society views AI-generated works in the future. This evolving landscape poses both challenges and opportunities for the creative industries, making it imperative for stakeholders to remain vigilant regarding the legal frameworks that govern their work.

See also State AI Laws for 2026 Announced: Key Regulations Impacting Hiring Practices

State AI Laws for 2026 Announced: Key Regulations Impacting Hiring Practices Vertex Expands AI Tax Compliance Partnership with CPA.com, Targets $27.86 Fair Value

Vertex Expands AI Tax Compliance Partnership with CPA.com, Targets $27.86 Fair Value