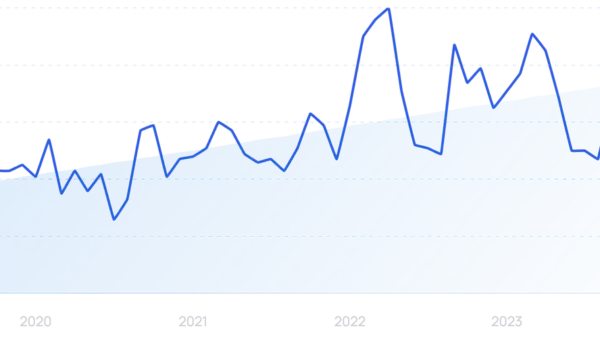

As universities increasingly integrate artificial intelligence (AI) into the educational landscape, a significant debate is emerging regarding its impact on students’ legal competencies. A recent report from the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) highlights that a staggering 88% of law students use AI for assessment-related tasks, marking a 66% increase since 2024. This trend raises crucial questions about the potential erosion of essential skills necessary for effective legal practice.

The HEPI/Kortext Student Generative AI Survey 2025 reveals a broader pattern among students across various disciplines, with 58% relying on AI to explain concepts and 48% employing it to summarize articles. The implications for law students are particularly pronounced, as traditional learning methods, which involve critical thinking, problem-solving, and effective communication, seem to be sidelined in favor of quick solutions provided by AI.

Law education has traditionally emphasized doctrinal knowledge, requiring students to engage with complex readings, participate in discussions, and apply legal principles through assessments and extracurricular activities. However, economic pressures are pushing students toward AI as a shortcut. According to the National Union of Students, 62% of full-time students work part-time jobs, limiting their time for academic engagement and contributing to a reliance on AI tools as a means of coping with demanding workloads.

Concerns About Cognitive Development

The overreliance on AI raises alarming concerns about cognitive development among law students. The first year of a law program is critical for developing analytical skills, including the ability to apply the law, interpret legislative intent, and construct persuasive arguments. Neuroscience research suggests that these skills are honed through persistent practice, and allowing AI to intervene at this stage may stifle independent legal reasoning. The current cost-of-living crisis exacerbates this issue, making it imperative for universities to reassess their assessment strategies to prioritize genuine understanding over mere completion of tasks.

Compounding the issue is the inconsistency in admission standards across universities. Only nine out of over 100 UK universities require law applicants to take the national admission test for law (LNAT), which assesses reasoning and analytical skills. This variability raises doubts about the preparedness of students entering law programs without such assessments, further emphasizing the need to restrict AI usage in foundational law courses.

From a technical standpoint, the limitations of AI-generated content are well documented. AI models can produce summaries that lack nuanced legal reasoning and may even provide inaccurate citations or flawed interpretations of case law. This detachment from judicial reasoning risks creating a generation of lawyers ill-equipped to navigate complex legal landscapes, potentially undermining the integrity of legal processes.

Recognizing the challenges posed by AI, experts suggest that while it cannot be entirely banned, measures must be implemented to mitigate overreliance. Universities could implement authentic assessments evaluated through in-person examinations or presentations to foster deeper engagement with course material. The Quality Assurance Agency has already called for innovative assessment strategies that encourage students to apply their knowledge in real-world contexts.

One proposal includes offering assessment exemptions based on participation in moot courts, allowing students to earn grades through practical legal experiences. Additionally, students could engage in patchwork assessments during internships or law clinics, whereby they submit formative pieces of work followed by reflective essays detailing their learning experiences.

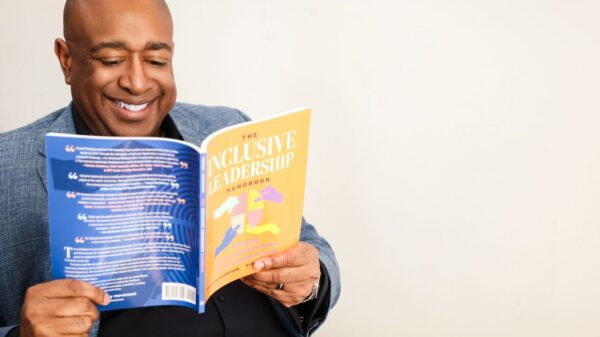

While the potential of AI to enhance productivity in legal practice cannot be ignored, it is crucial to delay its sanctioned use until students reach their second year. Programs like Alternative Dispute Resolution and Professional Skills could benefit from incorporating domain-specific AI tools, but only after students have acquired the foundational knowledge and skills needed to engage with technology meaningfully.

Effective communication remains a cornerstone of legal practice. Therefore, law schools should prioritize the development of strong oral communication skills, ensuring that all students, including those with special needs, receive the necessary accommodations. By doing so, universities can fulfill their moral obligation to produce competent legal graduates capable of navigating a complex and evolving profession.

As the debate surrounding AI in legal education continues, there is a pressing need for institutions to carefully consider the implications of technology on student learning. The move toward AI integration must be approached with caution to avoid compromising the essential skills that underpin effective legal practice, ensuring the integrity of law degrees and the competency of future lawyers.

See also K-12 Leaders Must Make 5 Key Moves to Effectively Integrate AI in Schools

K-12 Leaders Must Make 5 Key Moves to Effectively Integrate AI in Schools OpenAI Launches Australia’s First Sovereign AI Program with NEXTDC to Boost Local Infrastructure

OpenAI Launches Australia’s First Sovereign AI Program with NEXTDC to Boost Local Infrastructure Anthropic Reveals AI Workforce Trends from 1,250 Professionals in New Study

Anthropic Reveals AI Workforce Trends from 1,250 Professionals in New Study