At the INAH Yucatán Ichkaantijoo Symposium, researcher Benjamín González introduced a pioneering artificial intelligence model named Sáastun, designed to translate ancient Maya glyphs into English. The presentation, which took place in Mérida, Mexico, highlighted the potential of this technology amidst a backdrop of skepticism surrounding the complexities of Maya writing.

González emphasized that Sáastun is still an early prototype but has made impressive strides. The name “Sáastun” is derived from a divination tool historically utilized by Maya priests. Archaeologist Zachary Lindsey acknowledged the initial skepticism regarding the AI’s capabilities, noting the intricacies involved in interpreting Maya scripts. “Just how far it has already come is nothing short of amazing,” he remarked.

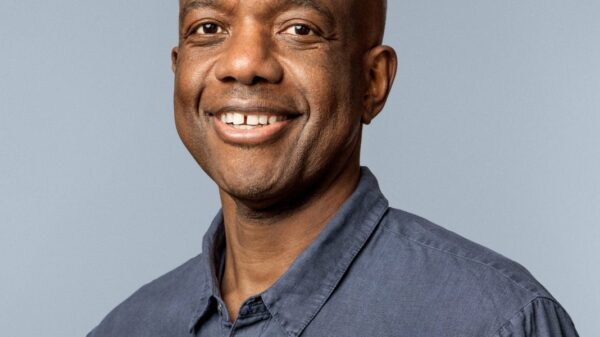

Rather than being an expert in epigraphy or archaeology, González is an engineer residing in Montreal, specializing in AI applications across various industries. He characterized Sáastun AI as a digital assistant for archaeologists, engineered to perform three main functions: identify glyphs in images, determine the meaning of each glyph, and translate the entire sequence.

While the AI model is not yet available to the public, González indicated that it will launch “not too long from now.” The initial step in his process involves isolating glyphs from their surrounding imagery, such as artwork or background patterns. Using over 2,000 training images, González’s system performs well but can occasionally misclassify decorative elements as written text, necessitating additional examples for clarification.

The next challenge involves arranging the identified glyphs in the correct reading order. This task is complicated by the fact that Maya scribes often wrote in intricate patterns rather than linear sequences. Currently, González’s methodology groups similarly sized glyphs, though he admits this technique requires refinement to accommodate diverse layouts.

A significant hurdle for Sáastun AI has been the recognition of individual glyphs, especially given the lack of extensive labeled image libraries. To overcome this, González utilized existing databases featuring expert-identified glyphs, training his AI with over 70,000 drawings. While it has shown proficiency in recognizing clean illustrations, Sáastun AI struggles with photographs of aged stone monuments, highlighting a critical area for future development.

Once glyphs are identified and arranged, the system performs translation by comparing the sequence against an extensive database of known translations. It searches for the closest match and then employs a modern language model to generate coherent English sentences. During his demonstration, González showcased the model’s ability to successfully translate a section of a Maya panel.

Despite its advancements, González remains candid about the system’s limitations. The AI can occasionally produce inaccurate results, a phenomenon referred to as “hallucination.” It does not fully grasp Maya grammar and the creative liberties taken by scribes in combining glyphs. Currently, it serves as a tool for suggesting possible interpretations rather than delivering definitive translations.

Nevertheless, the potential applications are vast. González envisions Sáastun aiding field archaeologists in quickly comprehending the content of inscriptions and potentially reconstructing fragmented monuments by proposing how pieces may fit together. On a broader scale, the AI could analyze large volumes of inscriptions to identify patterns and even infer meanings for eroded glyphs based on surrounding context.

Educational use is one of González’s most exciting prospects. He illustrated how Sáastun could integrate with virtual reality, allowing users worldwide to explore 3D representations of monuments and witness translations in real time. This could significantly enhance accessibility to Maya history for students and the general public.

Currently operating independently, González seeks partnerships with universities and archaeologists to enhance Sáastun AI. He stressed that the model’s improvement hinges on acquiring high-quality data, including photographs of monuments, codices, and pottery. “If we have the data, we can train a model,” he asserted.

With a strong connection to his roots, González expressed particular interest in collaborating with researchers and students in Mexico, stating, “All too often, we look to the rest of the world to advance our technology, but we are more than capable of doing it ourselves; though a little outside help never hurts.”

As developments in AI continue to evolve, Sáastun represents a significant intersection of technology and cultural preservation, potentially reshaping how ancient languages are understood and appreciated in the modern world.

NVIDIA, OpenAI, and IBM are among the companies pushing the boundaries of AI, each contributing uniquely to the field.

See also Duluth’s Anno AI and Spear AI Lead Military-Grade Testing for Autonomous Technologies

Duluth’s Anno AI and Spear AI Lead Military-Grade Testing for Autonomous Technologies Runway Reveals First General World Model GWM-1 with Gen-4.5 Upgrades for Real-Time Video Generation

Runway Reveals First General World Model GWM-1 with Gen-4.5 Upgrades for Real-Time Video Generation AI Revolutionizes Science: From Drug Discovery to Weather Forecasting, Boosting Economic Growth

AI Revolutionizes Science: From Drug Discovery to Weather Forecasting, Boosting Economic Growth EPAM Launches AI Agents, Approves $1B Buyback, Reshaping Investment Landscape

EPAM Launches AI Agents, Approves $1B Buyback, Reshaping Investment Landscape AWS Unveils Strands Agents and Bedrock AgentCore for Advanced Physical AI Integration

AWS Unveils Strands Agents and Bedrock AgentCore for Advanced Physical AI Integration