Prime Minister Kim Min-seok emphasized the urgency of artificial intelligence (AI) advancement at the 2025 JoongAng Forum, stating that “falling behind by one day in the age of artificial intelligence means falling behind by a generation.” His remarks come as nations worldwide intensify their investments in AI, though good intentions alone do not ensure the anticipated outcomes.

The United States plans to invest $500 billion (736.5 trillion won) in the large-scale AI Stargate project through 2029. This initiative includes the construction of 20 hyperscale AI data centers and an AX strategy to integrate AI across various industries. Moreover, the U.S. government is pursuing market liberalization and regulatory easing to stimulate AI development, with a goal of creating 100,000 jobs.

Meanwhile, Europe, traditionally cautious regarding AI, is pivoting. In October, the European Commission announced a 340 trillion won investment plan to implement AI in industries and public administration. France aims to emerge as Europe’s AI leader by investing 109 billion euros ($125.6 billion) in AI infrastructure, while advancing a three-stage strategy outlined in the 2018 Villani Report to integrate AI into research, development, and industry. German Chancellor Friedrich Merz has criticized the current state of AI development, which is largely dominated by the United States and China, underscoring the need for Europe to secure its technological sovereignty.

In China, the combined R&D budgets of central and local governments for 2025 are approximately 800 trillion won, with funding directed towards AI, biotechnology, quantum technology, and 6G. Private firm Alibaba has also announced plans to invest 75 trillion won over three years in cloud and AI infrastructure, with over 80 Chinese large language models (LLMs) competing in the market, including DeepSeek and Alibaba’s QwQ.

In contrast, South Korea’s government allocated 10.1 trillion won for AI in next year’s budget. Of this, 2.6 trillion won is earmarked for AI adoption within the public sector, while 7.5 trillion won is designated for talent cultivation. However, this budget represents only 1.4 percent of the country’s overall 728 trillion won budget. By comparison, the U.S. plans to devote 720 trillion won—7.7 percent of its federal budget—to AI next year, and China’s focus on R&D amounts to 15.4 percent of its combined central and provincial budgets.

At the Beijing Forum in early November, I had the opportunity to speak about AI-based future education alongside representatives from Peking University and other institutions. China’s educational landscape is already undergoing transformation through AI, as evidenced by its ability to analyze key concepts in middle and high school mathematics, providing personalized instruction in lieu of teachers. Edtech companies are utilizing AI to create dashboards that display students’ learning activities and assessments, even developing systems to analyze teachers’ voices from lectures to enhance their delivery.

AI competitiveness is generally determined by three key components: computing centers, data, and talent. However, a culture receptive to adopting these technologies is equally vital, as demand creation is as important as establishing computing centers. Even the most advanced technologies will falter if a market fails to materialize to generate demand. Current industrial technology policy highlights that demand-pull is often more crucial than technology-push.

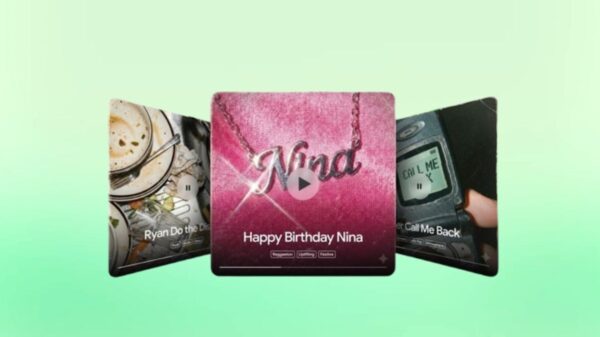

Despite a projected average annual growth rate of 15.9 percent in the global edtech market from 2025 to 2029—anticipated to reach 722 trillion won—Korea’s digital AI textbooks have not been adopted as official educational materials following a change in administration, resulting in their reclassification as teaching tools. Even with a 32.4 percent national adoption rate, variation exists, as adoption ranges from 98.1 percent in Daegu to 24.8 percent in Seoul. Edtech developers report losses of several hundred billion won due to these developments.

While insufficient prior communication with educators has been noted, there are concerns among teachers regarding their roles diminishing if AI textbooks take over knowledge delivery. In areas such as English and mathematics, AI could potentially handle formal knowledge dissemination, allowing teachers to concentrate on cultivating broader thinking and curiosity in students.

The repercussions of AI advances are evident in the workforce as well. Microsoft laid off 15,000 employees last year, primarily comprising software developers or support staff, as coding and programming tasks increasingly transition to AI capabilities. This shift raises concerns that graduate programs funded by the Ministry of Education may produce software developers rather than the innovative AI specialists required for the future. Just as architects are essential in constructing buildings, creative AI practitioners are seen as critical in this new landscape.

To foster AI development, Korea must actively leverage diverse data currently restricted by privacy and regulatory barriers—including hospital medical data, court precedent data, and corporate manufacturing data. Policymakers frequently discuss the concept of “signaling right while turning left,” highlighting a disconnect between the government’s stated intentions to promote AI and the tightening of regulations. This gap between policy and actual effects requires careful examination.

See also Insurance AI Regulations: 24 States Adopt New Compliance Standards Amid Data Privacy Challenges

Insurance AI Regulations: 24 States Adopt New Compliance Standards Amid Data Privacy Challenges AI Compliance Officers: Essential Role or Strong Governance Frameworks Enough?

AI Compliance Officers: Essential Role or Strong Governance Frameworks Enough? Trend Micro Launches Trend Vision One AI Security Package for Comprehensive AI Risk Management

Trend Micro Launches Trend Vision One AI Security Package for Comprehensive AI Risk Management India’s CCI Reveals AI Market Study, Proposes Policy for Fair Competition and Innovation

India’s CCI Reveals AI Market Study, Proposes Policy for Fair Competition and Innovation MSPs Prioritize Data Governance and AI Readiness Amid Rising Compliance Demands

MSPs Prioritize Data Governance and AI Readiness Amid Rising Compliance Demands