In the lead-up to the 2024 European Parliament elections, far-right political parties in France, Italy, and Belgium employed unlabelled generative-AI content to sway voters, despite their commitments to ethical campaigning. Investigations by DFRLab, Alliance4Europe, and AI Forensics uncovered 131 instances of undisclosed AI-generated or manipulated content across major social media platforms including Instagram, Facebook, X, Telegram, and Vkontakte.

The material varied from fabricated images and AI-enhanced visuals to shallowfakes and cheapfakes, which involved low-cost manipulations that paired misleading captions with out-of-context imagery. Researchers noted that this content was used to exacerbate social divisions, propagate conspiratorial narratives, and distort public discourse.

A post-election report from the European Commission supported these findings, indicating that political actors had utilized such content to “spread misleading narratives and amplify social divisions.” Civil society and fact-checkers identified more than 100 instances of unlabelled generative AI content shared by political parties, predominantly from France, Belgium, and Italy.

Contrary to concerns surrounding sophisticated deepfakes, most manipulations were basic and inexpensive, often featuring out-of-context captions, fabricated migration scenarios, and AI-enhanced images that promoted Islamophobic narratives, including the widely circulated notion of the “Muslim Great Replacement.”

The parties behind it

The electoral repercussions have been significant. Thirty-seven Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) elected during the campaign were affiliated with parties that utilized AI-generated or manipulated content: 29 from Rassemblement National (RN), eight from Lega, and one from Reconquête. Many of these lawmakers now occupy key positions on committees tasked with shaping the EU’s strategies concerning disinformation, digital regulation, and artificial intelligence, including LIBE, IMCO, and the newly formed Democracy Shield committee.

This situation creates a paradox for the EU, as legislators who were elected through methods deemed detrimental to electoral integrity are now responsible for crafting regulations intended to prevent such abuses. The use of unlabelled AI content also breached the 2024 European Parliament Elections Code of Conduct, signed by all political factions, including the far-right group Identity and Democracy (ID).

However, immediately following the elections, ID dissolved and reformed as Patriots for Europe (PfE), consolidating RN, Lega, and Reconquête without retaining ID’s commitments. The current European framework lacks mechanisms to penalize political actors for such violations. DFRLab researcher Valentin Châtelet noted that the code can only inform investigations under the Digital Services Act (DSA) and that the DSA targets platforms rather than political entities.

This discrepancy is mirrored in the European Commission’s April 2024 election guidelines for online platforms, which detail measures that Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and Very Large Online Search Engines (VLOSEs) should implement to combat disinformation and AI-generated manipulation. All recommendations are directed at platforms, not the political figures responsible for disseminating misleading content.

Civil society organizations argue that the EU is attempting to protect elections by solely regulating the infrastructure while neglecting the political actors who exploit it. These findings raise a critical question: how can the EU effectively regulate AI and disinformation when some lawmakers involved in drafting those regulations secured their positions partly through the use of unlabelled generative AI?

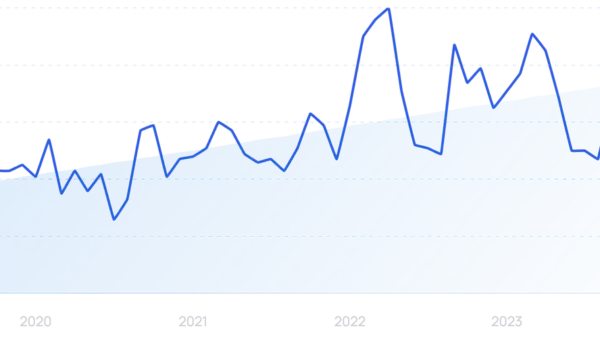

As political campaigns become more digitally oriented, researchers warn that Europe risks normalizing a model where AI-driven manipulation becomes commonplace in elections. The tactics observed during the 2024 European elections have not only persisted but have also escalated as national elections across Europe in 2025 have highlighted this issue in political communication.

For instance, in Ireland, a fake announcement circulated online claiming that a presidential candidate had withdrawn from the race. In the Czech Republic, analysts identified a surge of AI-manipulated content focused on migration, crime, and EU membership. Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, authorities and watchdogs have publicly cautioned against AI-driven manipulation, including misleading chatbots and algorithmic bias that could compromise informed voting.

Despite the severity of these incidents, the EU’s response has been limited to general warnings, without binding enforcement actions or political consequences for those behind the misleading content. The only comparable instance of annulled election results due to disinformation remains Romania’s 2024 presidential vote.

These occurrences underscore a broader existential threat across Europe. The responsibility for regulating these technologies partially rests with MEPs from parties that benefited from such tactics last year, highlighting a glaring disconnect as legislators in Brussels, elected through similar means, shape the rules designed to combat them.

See also Twelve AI Firms Release Updated Safety Policies Amid Growing Risk Concerns

Twelve AI Firms Release Updated Safety Policies Amid Growing Risk Concerns AI Safety Conclave Unveils Guidelines for Ethical AI Deployment in Critical Sectors

AI Safety Conclave Unveils Guidelines for Ethical AI Deployment in Critical Sectors New York Enacts RAISE Act Mandating AI Safety Reporting for Developers by 2027

New York Enacts RAISE Act Mandating AI Safety Reporting for Developers by 2027 Mississippi Lawyer Fined $20K for AI Hallucinations in Legal Documents

Mississippi Lawyer Fined $20K for AI Hallucinations in Legal Documents Trump Prepares Executive Order to Centralize AI Regulation, Blocking State Laws

Trump Prepares Executive Order to Centralize AI Regulation, Blocking State Laws