The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has sparked a belief that the future will be dominated by coders, data scientists, and engineers. However, as the past year has demonstrated, many of the world’s pressing challenges—from AI ethics to climate resilience—cannot be tackled solely with technical expertise. These issues reveal the limitations of a purely technocratic mindset. According to the World Economic Forum 2023, nearly half of all job skills are set to change within the next five years, prompting a critical reflection: Are we educating solely for employment, or are we preparing for the future of humanity?

While the concept of “liberal arts” is often articulated in Western terms, its foundational philosophy is deeply embedded in Chinese civilization. For millennia, China’s educational tradition has emphasized the cultivation of moral character, broad cultural insight, and sound judgment. Historically, many of China’s scientific breakthroughs were achieved by scholars whose humanistic backgrounds enriched their scientific creativity. For instance, Zhang Heng, a scientist from the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), is remembered not just for inventing the world’s first seismoscope but also as a poet and philosopher who perceived natural phenomena as part of a greater moral and cosmic order. Similarly, the innovative astronomical clock created by Su Song during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) emerged from a mind that intertwined disciplines such as classics, medicine, engineering, and cosmology. These figures exemplified broad thinking, whose achievements arose from integrating science with humanistic inquiry.

This historical context is particularly relevant today, as the challenges we face mirror those encountered by early thinkers at the brink of new technological possibilities. AI, despite its capabilities, cannot articulate why certain choices are just, the significance of traditions, or how societies should manage the long-term moral implications of innovation. While it can optimize decisions, it lacks the ability to assume responsibility for them. The humanities—encompassing history, literature, philosophy, ethics, and the arts—remain vital; they hone uniquely human capacities such as judgment, empathy, imagination, and the ability to contemplate values beyond mere outputs.

Despite this, higher education throughout much of the 20th century has leaned heavily toward specialization, efficiency, and vocational training. This approach led to economic growth but also resulted in a constricted intellectual landscape. Today’s multifaceted problems highlight the drawbacks of excessive specialization and the marginalization of the humanities: engineers may construct AI systems yet struggle to govern them; technologists modeling climate trajectories might find it difficult to mediate community interests; and analysts predicting behaviors could fail to interpret their significance.

Encouragingly, universities across China are revitalizing the humanities, moving them away from the periphery of academic focus. At Tsinghua University, philosophers and computer scientists collaborate to explore AI ethics, while Peking University and Fudan University are developing “new humanities” models that integrate history, literature, and moral reasoning with data science. Moreover, experiential learning—characterized by community engagement, project-based courses, and cross-disciplinary inquiry—is gaining traction in many academic settings. These advancements resonate with China’s enduring belief that education should cultivate virtue and develop talent, rather than simply impart technical skills.

The global trend is clear: universities embracing interdisciplinary approaches are seeing increased relevance. MIT‘s urban design labs merge social sciences with engineering, Ashoka University combines philosophy and public policy, and numerous European institutions are forging new fields like digital humanities, environmental ethics, and technology governance where humanistic insights shape scientific advancement. Countries that persist in isolating disciplines risk not only hindering innovation but also jeopardizing societal resilience.

Ultimately, the discourse surrounding the humanities extends into a broader conversation about the future we envision. A narrowly technical education may yield efficient systems but could also cultivate disconnected citizens. In contrast, integrating innovation with virtue—an ideal deeply rooted in Chinese intellectual heritage—could ensure that the technological landscape evolves to be not only smarter but also fairer, kinder, and more human-centered.

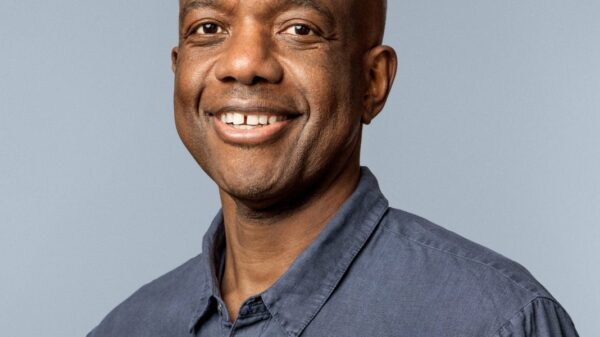

John Quelch serves as the executive vice-chancellor, American president, and distinguished professor of social science at Duke Kunshan University in China. Zach Fredman holds the position of associate professor of history and division chair of Arts and Humanities at Duke Kunshan University.

See also Australian Cyber Security Centre Reveals Key Principles for Safe AI Integration in OT Systems

Australian Cyber Security Centre Reveals Key Principles for Safe AI Integration in OT Systems Li Auto Launches Affordable AI Glasses Livis, Targeting 1.5 Million Car Owners

Li Auto Launches Affordable AI Glasses Livis, Targeting 1.5 Million Car Owners Microsoft’s Jenny Lay-Flurrie Reveals Key Strategies for Building Inclusive AI Tech

Microsoft’s Jenny Lay-Flurrie Reveals Key Strategies for Building Inclusive AI Tech Quantum Computing Faces Potential Bubble as 2026 Prototype Deadline Approaches

Quantum Computing Faces Potential Bubble as 2026 Prototype Deadline Approaches US and Allies Issue AI Guidance for Critical Infrastructure Operators to Mitigate Risks

US and Allies Issue AI Guidance for Critical Infrastructure Operators to Mitigate Risks