The Trump administration’s Pax Silica Initiative, launched on December 11, 2025, aims to strengthen the technology supply chain through a partnership between the United States and eight allied countries. This initiative underscores a belief that while the 20th century was powered by oil and steel, the 21st century is driven by compute and the minerals that support it. Just two days prior, the Linux Foundation announced the formation of the Agentic AI Foundation (AAIF), a consortium of major artificial intelligence firms like Amazon, Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Cloudflare. This group is dedicated to establishing a shared ecosystem for agentic AI, which refers to AI systems capable of performing tasks autonomously.

These recent endeavors contribute to a rapidly evolving and fragmented landscape of AI governance. Various international bodies and working groups have emerged, generating an increasing volume of normative texts and policy papers. Since 2024, the Council of Europe has finalized its Convention on Artificial Intelligence, and the OECD has updated its principles for trustworthy AI. Additionally, the U.S. has launched Pax Silica, and the United Nations has established an “Independent International Scientific Panel on Artificial Intelligence” to address governance issues. This proliferation of initiatives risks creating duplicative efforts, substantial overlaps in governance, and interoperability challenges, complicating the landscape for stakeholders involved in AI governance.

The United Nations has recognized these challenges, advocating for a “multistakeholder AI governance” approach, though without clear definitions of what this entails. In response, the authors of this article propose a multilayered framework to conceptualize global AI governance using a model adapted from the widely acknowledged three-layer framework for internet governance. This framework reflects the AI “stack,” encompassing hardware, software, data, and applications, as well as the essential materials and energy components.

A foundational element of internet governance, articulated by Yochai Benkler over two decades ago, distinguishes three layers of internet activity: the infrastructure layer, which includes physical components like servers and cables; the logical layer, encompassing software, protocols, and standards; and the content layer, representing the myriad human and organizational interactions over the internet. By applying this model to AI governance, the authors delineate the AI infrastructure layer as comprising the computing and data systems crucial for high-performance AI, while the logical layer encompasses AI models and software systems. The social layer captures the interactions driven by AI applications across various sectors.

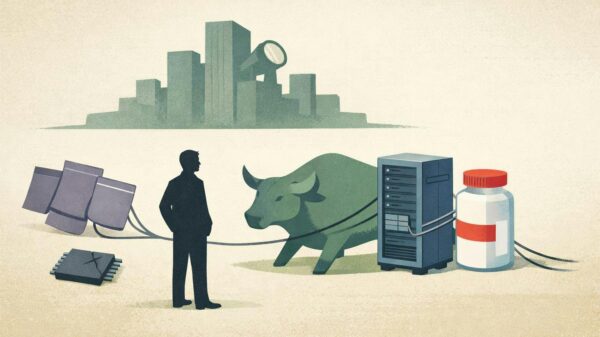

Each of these layers has its own set of relevant actors and institutions. For example, companies such as Nvidia and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) operate at the AI infrastructure layer, while proprietary models from firms like OpenAI and Google dominate the logical layer. The social layer sees a diverse range of applications spanning business and consumer interactions, from hiring tools to marketing strategies. This layered approach allows for a nuanced classification of policy initiatives, identifying where various regulations and frameworks focus their efforts.

Moreover, the framework highlights significant governance challenges ahead, especially as frontier AI companies increasingly aim to control the full “stack” of AI applications, including energy and computing infrastructure. Major players like Microsoft and Meta have made headlines with deals to secure energy sources for their data centers. Such strategic cross-layer collaborations complicate governance, as actors operate across multiple layers, further blurring the lines between AI infrastructure, logical systems, and social applications.

The implications extend beyond traditional governance models. Observations indicate that AI systems produce value across all layers, creating a continuous loop where policies impacting one layer can affect others. Regulatory frameworks regarding fairness, for instance, may necessitate changes in training datasets at the logical layer. This interdependence suggests that some AI domains might be better understood as cross-layer verticals rather than isolated categories, prompting a re-evaluation of existing frameworks.

While the UN could theoretically assume a greater role in AI governance, concerns about its bureaucratic nature and the risk of representing non-democratic interests complicate this scenario. As the international community navigates the complexities of AI governance, the challenge lies in balancing targeted, agile policymaking that fosters innovation while ensuring that fundamental rights are protected.

Looking ahead, the proposed three-layer framework could evolve to incorporate finer distinctions, such as a separate layer for foundation models or one addressing the physical systems that will increasingly integrate AI into daily life. Given the geopolitical implications of securing essential minerals for AI infrastructure, the need for a coordinated international approach is more pressing than ever. The framework serves as both a starting point and a call to action for stakeholders across the AI landscape, inviting contributions to refine and enhance its robustness in a rapidly changing world.

See also Tesseract Launches Site Manager and PRISM Vision Badge for Job Site Clarity

Tesseract Launches Site Manager and PRISM Vision Badge for Job Site Clarity Affordable Android Smartwatches That Offer Great Value and Features

Affordable Android Smartwatches That Offer Great Value and Features Russia”s AIDOL Robot Stumbles During Debut in Moscow

Russia”s AIDOL Robot Stumbles During Debut in Moscow AI Technology Revolutionizes Meat Processing at Cargill Slaughterhouse

AI Technology Revolutionizes Meat Processing at Cargill Slaughterhouse Seagate Unveils Exos 4U100: 3.2PB AI-Ready Storage with Advanced HAMR Tech

Seagate Unveils Exos 4U100: 3.2PB AI-Ready Storage with Advanced HAMR Tech