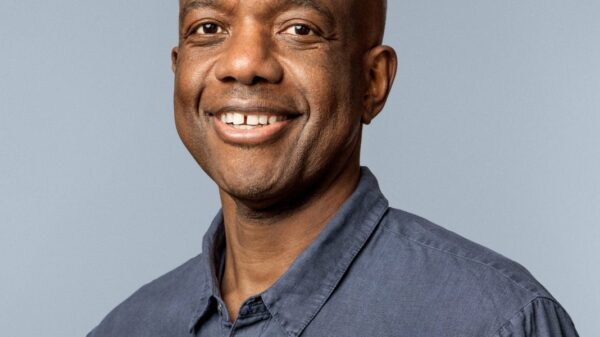

Lim Woong, a professor at the Graduate School of Education at Yonsei University in Seoul, recently conducted a thought-provoking experiment in his graduate seminar on AI ethics. He posed a simple yet revealing question to his students: “When you close your eyes and imagine a user for the AI system you are designing, whose face do you see?” The majority of students, aged primarily in their 20s and 30s, envisioned someone similar to themselves—young, tech-savvy individuals fluent in digital interfaces. Notably absent from their mental images were older adults, particularly their own grandparents. This moment of silence highlighted a significant blind spot in the conversation surrounding technology and its users.

The disconnection between technology design and the needs of older adults is a pressing concern, particularly as society increasingly values speed and efficiency. Hartmut Rosa, a German sociologist, describes this phenomenon as “social acceleration,” where everything moves rapidly, leaving little time for adjustment. In this climate, the wisdom and experience offered by older generations are often overlooked. Rather than being seen as mentors, older adults are frequently viewed as obstacles to the rapid flow of modern life, especially in contexts where technology is essential for everyday tasks.

This exclusionary mindset leads to what scholars term “heartless harm.” While the developers of AI systems do not intentionally aim to marginalize older adults, the outcomes can be devastating. For example, if a voice assistant struggles to comprehend a slower, shakier voice or if a smart home interface requires the eyesight of a younger individual, the result is a technological landscape that can alienate millions who are aging or living with disabilities.

To address these issues, the discourse around AI ethics must evolve, incorporating a new ethical vocabulary. This is where the concept of “gongsheng,” or symbiosis, becomes important. Introduced to Lim Woong by colleagues at Yonsei University, gongsheng is not merely about coexisting but about thriving together through interaction. According to Yiwen Zhan at Beijing Normal University, it represents a “co-becoming,” highlighting the necessity of mutual growth among diverse user groups.

Shoujun Hu from Fudan University further emphasizes that true gongsheng cannot exist without equality. Regardless of age or professional standing, relationships grounded in mutual respect are essential for a symbiotic relationship; otherwise, they risk becoming parasitic in nature.

This philosophical approach is being practically applied in Korea. Lee Yeun-sook, an emeritus professor at Yonsei University, has turned these ideas into actionable designs through her “aging in community” framework. Her premise is straightforward yet profound: aging should not equate to a shrinking world. Instead of the common phrase “aging in place,” which often implies solitary living at home, she advocates for a cohesive system involving homes, communities, and urban environments working in harmony. Her research indicates how technology can facilitate this interconnectedness, utilizing smart mobility systems that bridge a senior’s front door to local clinics, or AI-assisted planning tools that ensure equitable resource allocation.

The real challenge in AI ethics lies in questioning whether technology merely showcases intelligence or genuinely fosters relationships. Does an AI tool help an elderly person remain engaged with their neighborhood, or does it isolate them further? This shift in priorities in design is crucial, as it urges developers to focus on the margins rather than the so-called “average” user. If a technology is accessible for individuals with arthritis or low vision, it will inherently benefit a broader audience.

Despite this insightful discourse, some students in Lim Woong’s class found it challenging to embrace this paradigm shift. He prompted them to envision their mothers waiting at a winter bus stop, where service information is represented only by a QR code and heating is activated through an NFC-enabled screen, all the while grappling with cold hands and forgotten reading glasses. This exercise underscored the limitations of efficiency-driven design. Ultimately, each student will one day inhabit a similar role, struggling with the evolving interface of technology.

Korea, with one of the fastest-aging populations globally coupled with advanced digital infrastructure, has a unique opportunity to serve as a testing ground for these crucial questions. By proving that technology can enhance dignity rather than diminish it, the country stands at the forefront of redefining AI ethics.

As society navigates this landscape, the true measure of AI ethics will not be in passing the Turing Test but in the ability to create systems that are inclusive and supportive. The philosophy of gongsheng serves as a guiding principle, reminding us that we are not just individuals racing toward the future but part of a community that must journey together. If we can develop AI with this ethos, we may pave the way for a future that embraces every generation.

For further insights on AI ethics and technology design, visit: Yonsei University, Beijing Normal University, and Fudan University.

See also US Tech Giants Invest $200B in Europe’s AI Boom, Redefining Global Innovation Landscape

US Tech Giants Invest $200B in Europe’s AI Boom, Redefining Global Innovation Landscape Fed Vice Chair Philip Jefferson Warns AI’s Economic Impact Could Strain Financial Stability

Fed Vice Chair Philip Jefferson Warns AI’s Economic Impact Could Strain Financial Stability Idaho Launches ‘Hour of AI’ to Equip Students for Future Tech Careers Amid Rapid AI Growth

Idaho Launches ‘Hour of AI’ to Equip Students for Future Tech Careers Amid Rapid AI Growth Anthropic Reveals New Agent Mode for Claude with Task-Oriented Features and Avatars

Anthropic Reveals New Agent Mode for Claude with Task-Oriented Features and Avatars