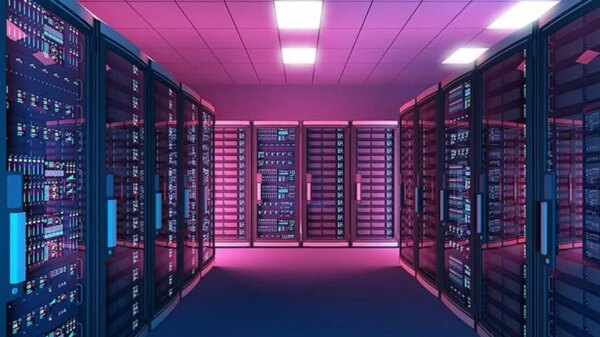

Strange though it may seem, the best view in Ireland of the unfolding global investments in artificial intelligence (AI) is from a hiking trail looking down at the city from the Dublin mountains. The hulking shapes of data centres, visible from these heights, serve as local evidence of the international frenzy over AI, which its proponents assert will drive productivity and reshape the global economy.

Billions of private investments are flowing into the development of AI chipsets and the considerable processing power needed to handle new forms of data. However, the AI revolution is not solely about software and algorithms; it necessitates the physical infrastructure of energy-hungry data centres, like those observed from the Dublin mountains.

Large amounts of public funding are also at stake. AI processing will require more electricity, likely sourced from both renewables and fossil fuels. Supplying that power to data centres involves reconstructing power lines, which will inevitably draw from public resources. This scene sets the stage for a traditional clash between public and private interests, particularly in Ireland, where major technology firms significantly contribute to government revenues.

In fact, around a third of all state tax revenues in 2025 is projected to come from corporate taxes, mainly paid by the small cohort of US giants now engaged in the AI investment race. The demands of AI appear to have only strengthened the influence of these multinationals on public policy in Dublin, creating concerns among Irish-owned small firms and climate activists about who truly benefits from substantial public investments in offshore wind farms and new power grids.

Critics worry that a considerable portion of the island’s promised renewable energy will be consumed by foreign-owned AI data centres. A 2024 survey indicated that there were already approximately 80 data centres operating in Ireland, with 40 more centres securing planning permission at that time. Most of these data centres are concentrated around the capital, while a smaller cluster exists in Belfast, with some additional facilities in Cork, Galway, and Kilkenny.

However, the construction of new data centres is often entangled in a slugging match involving the world’s largest companies and influential business lobby groups. The Irish government and its regulators are tasked with overseeing public investments in clean electricity alongside carbon-reduction targets, which often seem at odds with the escalating demands of new AI data centres.

Official policy is further complicated by public obligations to maintain future economic health, primarily through the Government’s Industrial Development Agency (IDA), which encourages foreign tech investments. Figures from the Climate and Energy Division of the Central Statistics Office reveal that data centres accounted for 22% of all electricity consumed in the Republic in 2024, a significant increase from 5% in 2015. Additionally, recent CSO data positions the Republic as having the second-highest greenhouse gas emissions per capita in the EU in 2023.

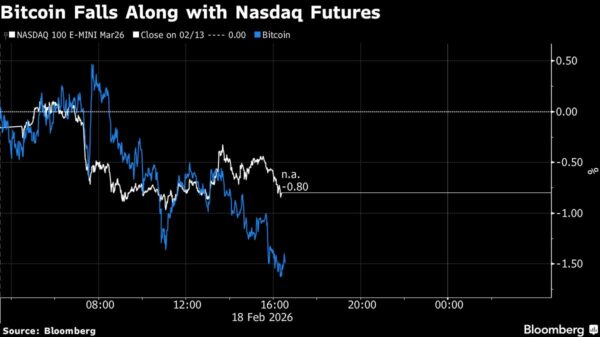

Recent business headlines indicate that the mega companies driving the AI investment boom are gaining the upper hand. Before Christmas, Google-owner Alphabet announced plans to acquire data centre firm Intersect for $4.75 billion. On the same day, US data hinted that spending on data centres significantly contributed to economic growth.

Meanwhile, AI chipset producer Nvidia recently finalized a $5 billion investment in rival chipmaker Intel, which employs nearly 4,900 people at its facilities in the Republic, including a major plant in Leixlip. Bloomberg reported that AI investments fueled approximately $70 billion in data-centre deal-making in 2025, while SoftBank offered $4 billion for DigitalBridge, involved in the booming data centre market in Texas.

Back in Ireland, analysts are closely monitoring plans by Kingspan, based in County Cavan, to sell shares and potentially spin out its data-centre outfitter Advnsys unit for around €6 billion (£5.2 billion). This move will test whether the €13.3 billion insulation products giant can successfully tap into the data centre investment boom.

Moreover, significant news has emerged from the Irish government regulator, the Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU), which has established new rules for data centres connecting to the power grid. While it remains to be seen how effective these regulations will be, the business group Wind Energy Ireland, which encompasses a variety of stakeholders in the renewable sector, has expressed support for the CRU’s policies.

Conversely, environmental advocates, including Friends of the Earth, have criticized the stark energy demands of the new wave of data centres, arguing that it will severely impact all forms of energy generation, whether from wind, solar, or fossil fuels. As Amazon Web Services recently secured planning permission for three new data centres in Dublin, it is clear that views from the Dublin mountains will feature even more of these large structures in the coming years.

As the landscape of Ireland continues to transform under the weight of AI investments, the balance between economic growth and environmental sustainability remains a pressing concern for the future.

See also Meta Acquires AI Startup Manus for $2B Amid Capital Pressure on Tech Sector

Meta Acquires AI Startup Manus for $2B Amid Capital Pressure on Tech Sector Ethiopian Researchers Leverage Machine Learning to Predict Prolonged Hospital Stays, Transforming Resource Management

Ethiopian Researchers Leverage Machine Learning to Predict Prolonged Hospital Stays, Transforming Resource Management Kingsley Association Unveils Charly: Its First Digital Chatbot Employee, Revolutionizing Engagement

Kingsley Association Unveils Charly: Its First Digital Chatbot Employee, Revolutionizing Engagement AI Models Misjudge Exam Difficulty, Underestimate Human Struggles, Study Finds

AI Models Misjudge Exam Difficulty, Underestimate Human Struggles, Study Finds