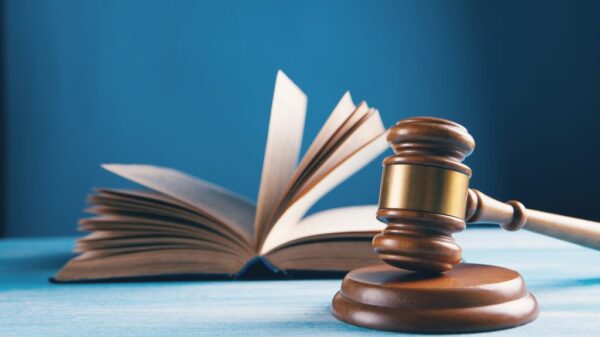

In a landmark ruling earlier this month, the court delivered a verdict in the pivotal copyright case of Getty Images v Stability AI, a decision that promised to clarify the legal ramifications surrounding AI model training and copyright infringement. However, the outcome left many in both the creative and AI sectors seeking clearer answers, as fundamental questions about copyright were largely left unresolved.

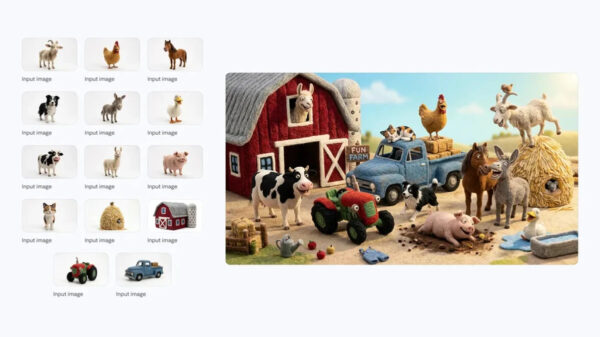

At the heart of this case was the contentious use of Getty Images’ expansive photo library by Stability AI to train its AI model, Stable Diffusion. Getty Images described this library, established in the 1990s with funds from the Getty family, as its “lifeblood.” Stability AI utilized images from this collection without obtaining prior consent, and notably, the training occurred outside the UK.

During the trial, Getty Images presented evidence claiming that specific generated images from various iterations of Stable Diffusion could be traced back to its library, with some outputs even reproducing Getty Images watermarks. This seemingly bolstered Getty’s claims of copyright, database right, and trademark infringement, along with passing off. However, the court noted significant gaps in Getty’s case. Notably, Getty conceded that there was no proof demonstrating that the training and development of Stable Diffusion took place within UK jurisdiction, leading it to abandon that claim. Furthermore, Stability AI had blocked user prompts that could generate the contested outputs, which prompted Getty to withdraw its copyright infringement claim regarding the AI outputs altogether.

Ultimately, Getty was left with a trademark infringement claim related to the watermarks on the AI outputs, alongside a contention that the Stable Diffusion model itself constituted an infringing article. This raised critical questions about whether Getty’s licensed photos allowed for concurrent rights with the photographers, thus entitling it to seek remedies for copyright infringement. The key victory for Getty, albeit limited, was a judicial acknowledgment that creators of AI models could be held liable for infringing outputs generated by their tools.

The court’s findings focused on instances of “double identity” and “confusion” trademark infringement, as delineated under sections 10(1) and 10(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994. Nevertheless, Getty was unsuccessful in its “detriment” claim under section 10(3) of the Act and in its passing off claim. The trademark infringement verdict came as no surprise, given the evident reproduction of Getty’s trademarked names in the watermarks on AI-generated images. However, the judge emphasized that these findings were both “historic and extremely limited in scope,” implying they would unlikely result in substantial damages for Getty when the quantum is eventually determined.

Legal experts glean from this that a clear connection between an intellectual property right and an AI output can lead to liability for the AI company in cases of infringement. For instance, one might envision a scenario where singer Taylor Swift could pursue legal action against an AI song generator for outputs that replicate significant portions of her existing work. However, questions linger, such as whether the AI outputs could be defended as “parody” or “pastiche,” possibilities not addressed in the Getty case.

Though it was determined that Getty Images had exclusive control over some of the disputed photos, its claim of secondary copyright infringement ultimately failed. The crux of the matter rested on the court’s determination of whether an AI model could be classified as an “infringing copy” under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998. Getty argued that the act of training involved reproducing photos, thus meeting the definition of an infringing copy. Stability AI countered that its model was trained on copyrighted works in the US, asserting that since copies of those works were never present in its AI model, it could not be deemed an infringing copy. The judge sided with Stability, declaring that Stable Diffusion “does not store or reproduce any copyright works” and thus fails to qualify as an “infringing copy.”

The ruling underscores a significant transformation in the digital landscape, highlighting a complex interplay between traditional intellectual property principles and innovative technologies. As data emerges as the new oil, the Getty Images case signals that while the path forward in defining copyright in the realm of AI remains fraught with challenges, the implications of this ruling will resonate throughout future legal disputes involving artificial intelligence.

See also Boost Employee Engagement: How AI-Driven Benefits Platforms Transform Utilization Rates

Boost Employee Engagement: How AI-Driven Benefits Platforms Transform Utilization Rates Emirates Partners with OpenAI to Enhance Operations and Customer Experience with AI Integration

Emirates Partners with OpenAI to Enhance Operations and Customer Experience with AI Integration Vertiv Unveils AI-Ready Data Center Solutions for Africa’s 50kW Rack Demands

Vertiv Unveils AI-Ready Data Center Solutions for Africa’s 50kW Rack Demands AI System Boosts Sole Aquaculture Efficiency by Predicting Spawning with 90% Accuracy

AI System Boosts Sole Aquaculture Efficiency by Predicting Spawning with 90% Accuracy AI Surge Sparks ‘Resource Grab’: Hedge Fund Veteran Warns of Talent Bottlenecks and Market Risks

AI Surge Sparks ‘Resource Grab’: Hedge Fund Veteran Warns of Talent Bottlenecks and Market Risks