Edward Egan

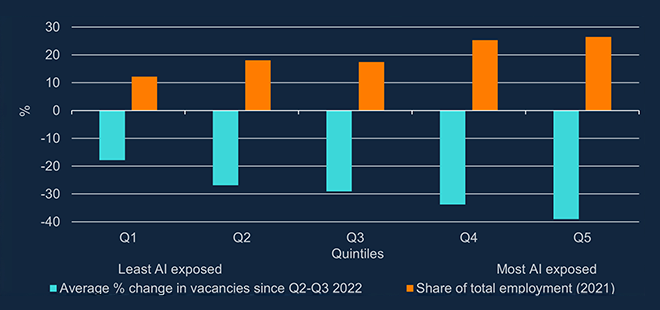

Concerns about a so-called “jobpocalypse” due to generative AI are emerging, but recent analyses suggest the reality is more nuanced. Instead of an unmitigated wave of job losses, research indicates that generative AI could impact the labor market through a variety of channels: productivity gains, job displacement, new job creation, and shifts in job composition. The interplay of these factors, rather than displacement alone, will dictate AI’s overall effect on employment. Recent data reveals that since mid-2022, online vacancies in roles highly susceptible to AI have decreased at more than double the rate compared to those in less exposed jobs, emphasizing the need for continued monitoring as AI adoption ramps up.

To navigate the intricate question of AI’s impact on employment, a ‘task-based’ framework can be beneficial. Developed by economists Acemoglu and Restrepo (2019), this approach focuses on the specific tasks that make up jobs rather than broad categories. For instance, in the finance sector, AI can automate data collection and reporting for junior analysts, while senior portfolio managers might leverage AI for market sentiment analysis or risk scenario simulations. This task-oriented view helps explain why some roles face displacement while others may benefit from increased productivity, even within the same industry.

We can categorize the channels through which AI might influence the labor market into four main effects. First, productivity augmentation: AI enhances worker productivity by automating repetitive tasks, allowing for a focus on more valuable activities. This expansion can subsequently boost demand for labor in non-automated tasks. Second, displacement: AI may automate a significant portion of tasks in specific roles, reducing demand for labor in those positions. Third, reinstatement: technological advancements historically generate new tasks that were previously unimaginable. In the current climate, this may manifest as a growing demand for roles that facilitate the integration of AI into organizational workflows, such as Forward-deployed Engineers. Finally, compositional effects refer to the potential reallocation of jobs across sectors, with some industries contracting while others expand, necessitating workforce retraining.

Much of the public discourse centers on the displacement channel, but the long-term net impact of AI on employment hinges on the balance between these effects, as well as the pace of AI development and adoption. This complexity adds a layer of uncertainty to understanding how these dynamics will evolve.

So far, evidence regarding AI’s impact on employment in the UK remains limited. A recent Decision Maker Panel Survey found minimal effects from AI on employment, with only a slight reduction expected in the coming years. Similarly, the Business Insights and Conditions Survey indicated that only 4% of firms utilizing AI (23% of all firms) reported workforce reductions attributable to AI, while just 7% of prospective adopters anticipate similar cuts. Contrastingly, data from Indeed has shown a rising demand for AI-related skills in the UK, suggesting early indications of the reinstatement effect as new tasks requiring AI competencies emerge.

In the U.S., researchers at the Yale budget lab observed similar trends, reporting no substantial disruptions to the aggregate labor market thus far, attributing some shifts in job composition to factors predating AI’s widespread adoption. Although some have linked the uptick in youth unemployment to AI, studies by the Economic Innovation Group and the Financial Times suggest macroeconomic conditions are likely more influential. Encouragingly, survey data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York indicates that many AI-using firms are prioritizing staff retraining over layoffs, highlighting that displacement is just one facet of AI’s labor market influence.

Recent analyses point to a noticeable slowdown in hiring within AI-exposed occupations, particularly affecting junior roles. Data indicates that new online job postings for highly exposed positions have fallen by nearly 40% since mid-2022, a decline more than double that of less exposed roles. This trend aligns with findings from McKinsey, although it may also reflect broader cyclical economic conditions rather than a direct causation from AI.

Future forecasts regarding AI’s potential to displace jobs vary widely, with projections for the UK ranging from negligible to approximately eight million job losses over the long term. However, many analyses suggest that these losses may be largely mitigated by the creation of new roles and enhanced productivity, echoing historical patterns following previous technological advances. The primary risk lies in the possibility that productivity gains from AI could be less robust than anticipated, alongside the challenge of creating new roles quickly enough to counterbalance those lost to automation.

In conclusion, current evidence indicates that while AI has not yet significantly altered overall labor market dynamics, there are indications of an amplified slowdown in hiring for AI-exposed occupations. As the technology evolves, its broader impacts may become evident, particularly if anticipated productivity improvements do not materialize or if the creation of new roles lags behind job displacement. Continuous monitoring will be essential to decipher the multifaceted effects of AI on the labor market and to ensure a smoother transition to an AI-enhanced economy.

Edward Egan works in the Bank’s International Surveillance Division.

See also Arizona State U. Launches AI Challenge: Students Develop Tools to Transform Campus Life

Arizona State U. Launches AI Challenge: Students Develop Tools to Transform Campus Life Nvidia’s Jensen Huang Visits China Amid H200 Chip Sales Restrictions and Market Challenges

Nvidia’s Jensen Huang Visits China Amid H200 Chip Sales Restrictions and Market Challenges India’s AI Impact Summit 2026: Pioneering Inclusive Growth for the Global South

India’s AI Impact Summit 2026: Pioneering Inclusive Growth for the Global South Anthropic Reveals 49% of U.S. Jobs Now Use AI for Key Tasks, Not Replacement

Anthropic Reveals 49% of U.S. Jobs Now Use AI for Key Tasks, Not Replacement